Introduction1

In September 2024, Yagi, the strongest typhoon to hit the South China Sea in the last 30 years (Hồ and Hiếu 2024), caused nearly 40,000 trees in Hanoi to fall (Bạch 2024). This created many empty spaces with a size of at least 1.44m squared2 scattered throughout the city. The trees were not immediately replanted, and the voids thus became subject to human and natural forces, transforming themselves into a particular kind of space in the urban landscape. The holes exist in the middle of the pavement, strangely uncanny and without official status, yet provide a centre stage for the emergence of different activities.

The void is not a vacuum or a space completely empty of matter or, as Lopez-Pinero puts it, ‘emptied of value associated with cities as places of capital accumulation’ (2020: 122). It is within this condition of being marginalised and forgotten in terms of use that the urban void becomes a respite, a break from the domination of the cityscape. It is, therefore, a horizon of imagination, possibilities and richness, henceforth bringing about intriguing observations and thoughts. Consequently, considering the post-typhoon tree holes as a performative stage of urban voids is not an attempt to label and define what they are, but to see them in their ambiguity, contradiction and pending existence; this is what excited me the most.

Methodology

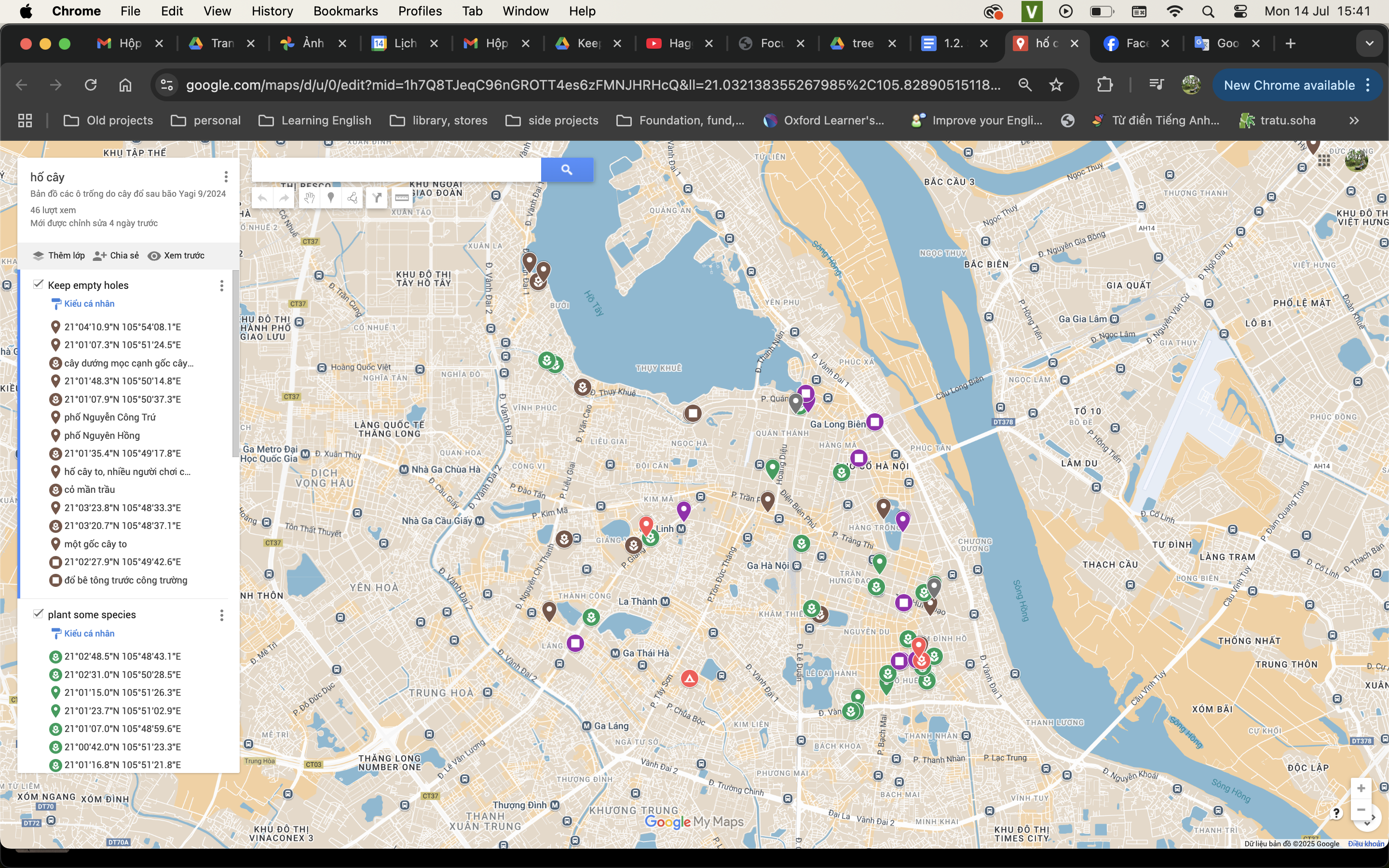

I first began noticing the holes left by uprooted and fallen trees on 10 September 2024, shortly after the typhoon had wreaked havoc. I was captivated by these last traces of the storm on the pavement – the voids – which soon led me to reflect on the phenomena unfolding in response to the absence of urban trees (Figures 1 & 2). As I gradually realised that many of these sites had yet to be replanted, I began photographing and mapping the tree holes on Google MyMap, focusing mainly on Hanoi’s city centre – particularly the areas I frequented, including the Nguyễn Công Trứ collective housing area, as well as Thuỵ Khuê and Láng Hạ streets. My close observations of these sites, along with the ongoing process of mapping them over a ten-month period (September 2024 to June 2025), eventually took clearer shape in April 2025, within the scope of the Song of the Wind project in Hanoi.

The map in Figure 3 is categorised using colours and symbols. These colours indicate three primary ways in which the holes have been configured: green signifies sites where local residents have planted new trees or plants, purple denotes those that have been covered with other materials, and brown marks the holes that have been left untouched. Each hole has its own context, and I used a set of symbols, including a flower (indicating sites that have been replanted not with urban species but with plants more closely connected to local lifestyles), a square (where the holes have been filled with hard materials), and a tent icon, which marks locations where residents have built kiosks on top of holes once occupied by old colonial-era xà cừ (nacre) trees.

The oscillating Temporalities of the Tree Holes

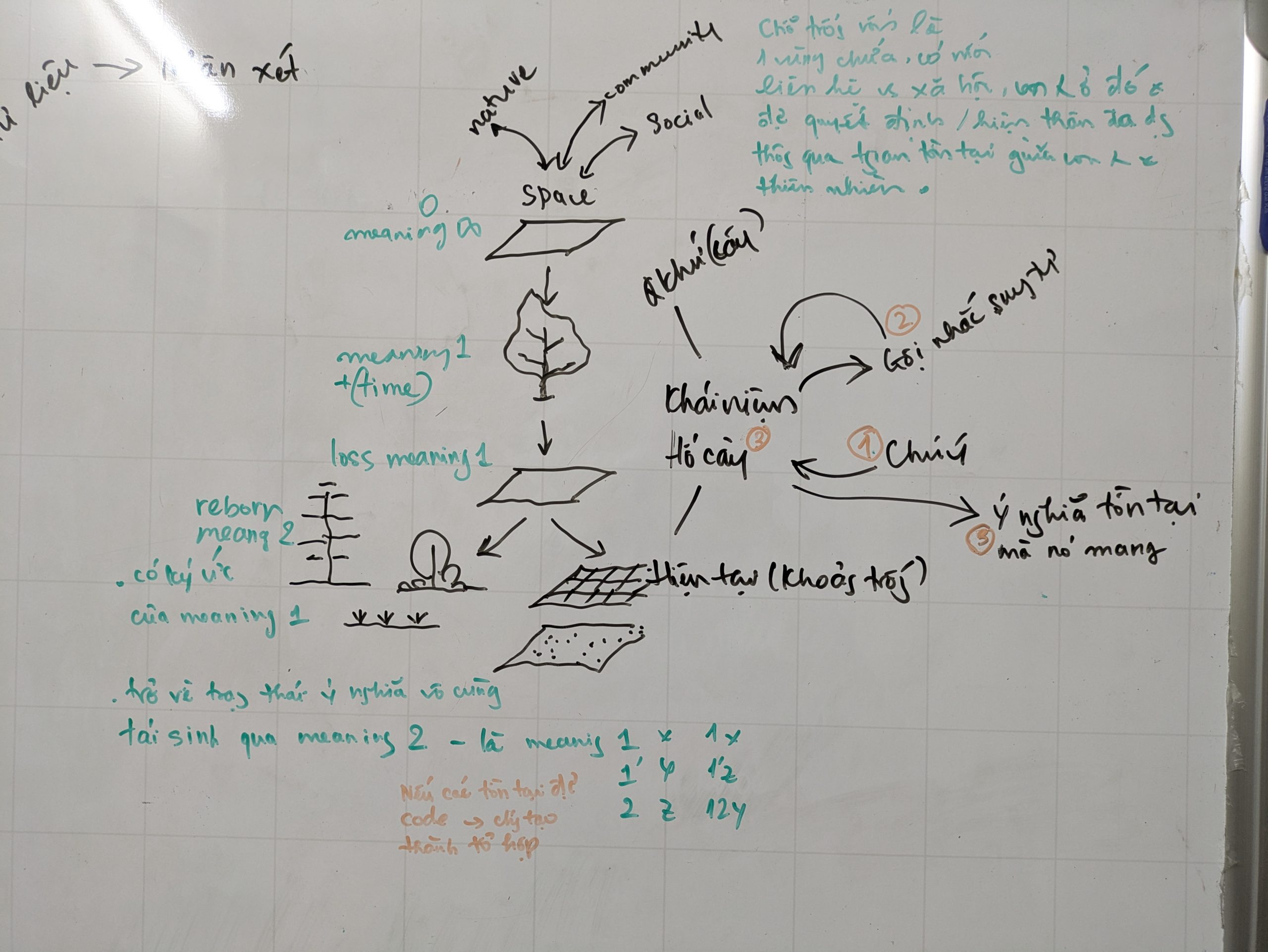

I think of a tree hole as something oscillating between multiple statuses and temporalities: a past embodying an urban tree, a present as a void and a future of unknown intention. The tree holes signify what they used to carry – the urban trees – a landscape feature closely tied with humans that has since been blown away by a raging typhoon. They are empty graves of absent dead trees, since their bodies were essentially carried away, buried, or laid to dry in a deserted park. At the same time, these patches of soil return to the status of a ‘non-functioning’ area, as marginal voids amidst compacted and occupied spaces.

This preoccupation with utility takes us back to the French urbanisation of Hanoi starting in 1890, which assigned almost every corner of this locality a specific function and thus deemed empty land areas useless (Fanchette et al 2016: 78). It should be noted that before French colonialisation, Hanoi was a city abundant with empty and non-functioning spaces which allowed the city a certain degree of flexibility. However, as the Hausmann style was imposed by the French onto the urban planning of Hanoi, almost every trace of the city’s earlier blueprint of citadels, towers and palaces was destroyed, which also demonstrated that even such structures were deemed empty spaces – empty of values and expectations. Going beyond this notion of capital accumulation and urban thinking about emptiness, I consider the tree hole as a void that functions in a way that opens up possibilities for different temporal and spatial conditions to seep in.

The tree hole traverses an ambiguous zone of management. In the case of an urban tree, the hole is under the management of the Green Tree and Environment Company. As a void, however, it is no longer taken care of in an urban manner. Henceforth, it exists as a space yet to take shape where anyone can exert influence. Within this particular setting, the tree hole can transform into anything. Thus, it is an ongoing impromptu theatrical stage that mourns loss, suggests a certain past and reflects different urban conditions (Figure 4).

Stage of Lamenting

The night after Yagi hit, Hanoi people were already mourning lost trees. Regardless of the active typhoon, traffic jams, and the heavy rain and flood that came with it, people went out to count how many trees had fallen, providing updates on social media and coming up with solutions to address their loss. This is not the first time Hanoi trees received such wide attention from the general public; 2015 saw a remarkable demonstration, whereupon the city authority decided to replace 6,708 urban trees (Vũ 2017). This affection for urban trees is partly attributed to the fact that they have been inseparable from the French colonial construction of Hanoi identity a century ago, as ‘a garden city’ of tropical species (Poulle 2001). Under this urbanisation project, the memories and aesthetics attached to Hanoi city are inextricably associated with urban trees (Nhân Dân 2020). Their loss was pervasively experienced when it was stated that only 3,000 of the city’s 40,000 trees survived after Yagi. Thousands of tree holes were thus laid bare while the remains of their dead bodies were quickly removed to clear the roads. For lack of a better term, thousands of ‘empty graves’ or ‘fake coffin holes’ were all of a sudden apparent, evoking people’s personal memories.

Yet, a question arose as to whether this was a stage of belated lamentation, and whether the affection for Hanoi’s trees had in fact been rather nonchalant. The uprooted trees revealed their once invisible wounds — the result of repeated root trimming carried out for the sake of urban maintenance — and one can still discern these injuries by observing the enduring cuts in the roots of the fallen trees. In Hanoi, urban trees had been simultaneously living and dying. During the Song of the Wind project in Hanoi, Nguyễn Hoàng Hào, a specialist from the Forest and Resource Museum, explained that ‘a tree canopy is proportional to its roots, the more expansive the roots get, the wider the canopy becomes’. Hanoi trees, however, are stranded within ongoing and unplanned sidewalk renovation, underground sewage construction, by cable replacement at their roots and with their branches pruned for security reasons. Deprived of time to recover, the trees get weaker and weaker, as if they were sticks tucked into a piece of soil. Thus, the Yagi in a way put an end to the urban trees’ gradual and unavoidable death, as opposed to their counterparts that are thriving again in the garden of the museum where Hào works. Yet, urban trees in Hanoi bear a romanticised expectation of living to the fullest; they emblematise the city’s identity and cater for human life, they are taken for granted and treated no better than insentient objects. Their uprooting and dislocation has turned the remaining holes into spaces demonstrative of this maltreatment, and evidence of a systematic ignorance and underlying suffering disguised in the name of modernity. This stage of lamenting comes with loss and gain, nostalgia and self-actualisation and an intriguing platform for further meaning-making and retrieval.

Stage of Meaning-making

Most of the pavement area in the city used to be part of pre-colonial Hanoi, an agrarian city that brought together villages, citadels and rice fields. Thus, the pavement construction, part of the colonial city planning project, erased traces of this unique landscape and imposed the very first notions of a modern city space. Yet, when the typhoon took away urban trees, the voids left behind continued, on the one hand, to carry the meaning of the absent trees, and on the other to perform varying configurations of đất hoang (unoccupied land) and cỏ dại (wild weed), of extended domestic space and even disappearance. Under these conditions, projections of different urban traits and their entanglement with local residents’ lives are revealed. It should be noted that this meaning-making evaded top-down management, since governmental campaigns only deal with people, not trees. And, as mentioned above, municipal environmental staff only take care of living trees and not holes without trees. Thus, there is a certain freedom and grassroots incentive iton how these spaces are formulated as independent micro-spaces, crisscrossing with diffracting forces. The tree holes are hardly empty but rich in the performative potential of meaning-making.

On Láng Hạ street, with its density of skyscrapers, office buildings and high-end residential complexes, the holes have been replanted or have become part of the pavement (Figures 5 & 7). The chosen plants are new, interbred species with different shapes and colours, and cultivated with calculation. Thus, the holes are adjusted and neatly decked to fit the modern spaces, which differ significantly from those in the old-quarter areas, namely Nguyễn Công Trứ street and Huế street, where people still live in ground-level houses and engage with the tree holes in a much more organic and spontaneous manner (Figure 8). There, people have brought their plants out of their domestic space into the unoccupied holes, extending their living area. This results in a wide range of plants and trees emerging according to each family’s taste instead of urban standards, ranging from ornamental plants, culturally significant plants (cây quất, the kumquat tree which households buy for the Lunar New Year), fruit plants (giàn mướp, sponge gourd vine) to flowering trees (lộc vừng, freshwater mangrove, hoa nhài, jasmine). Embodying these household miniature landscapes, the tree holes transcend and permeate into the richness of local life (Figure 6). In this way, the void becomes a space generating new meanings in different forms as it settles, while at the same time maintaining and continuing the memories attached to its former tree.

There is a particular case in the Nam Đồng collective housing area where a tree hole was completely covered by the replacement of a kiosk serving a private family business (Figure 9). Such a seemingly blatant act of turning a shared space into a personal possession, however, is by no means an unprecedented incident, given that the yards of collective housing areas have steadily been encroached upon for personal use for over 20 years. In their performative potential, the tree holes sustain and encompass contradictory phenomena. They are a site of contestation, on the one hand steering away from urban rationality and on the other reinforcing it, both retaining memories and washing them away. To say that the hole stages a ‘performative’ act does not necessarily mean that it is alive or contains a living entity. The hole still performs, even though it has been turned into a completely concreted-over void, totally evaporating as if no one knew it ever existed prior to the kiosk appearing in its place. It performs forgetting, and through being forgotten, it is reincarnated to partake in people’s extended living space.

This prompts us to think further about how a tree hole, or more generally an urban void, only continues to exist as long as it retains its physical boundaries, while its capital value is forgotten. In other words, as long as people remember it as something worthy of extraction and exploitation, it will no longer exist as a visible piece of soil but be changed into something else. It exists because people forget and it ceases to exist when people remember.

Stage of Revealing a Distant Past

Sliding back and forth between remembering and forgetting, the trees and plants grown by the local residents in the tree holes subtly carry traces of a village culture, as they represent small-scale gardening customs. In this sense, they stage ideas of a landscape before urbanisation and population migration into the city, and continue to take shape within this new context of post-Yagi tree holes. In an empty square on Trần Nhật Duật street, a cây hoa nhài (jasmine tree) grows in front of a motorbike repair shop, in another one on Cửa Đông street, a sponge gourd vine stands in the middle of the pavement; neither are pruned, and wild grass still grows. The holes are ‘fed’ with leftover tea leaves, a common natural fertiliser recycled from early morning tea-drinking habits. These species, as well as how they are cultivated and taken care of, are typical of the gardening practices of agricultural villages rather than those of a modern city.

In this space of local lifestyles, there are kumquat trees, which households would normally throw away after the Lunar New Year. Emblematic of nobility and prosperity, people would buy a kumquat tree abundant with fruits and budding blossoms for the Lunar New Year to bring luck and fortune to the home. Twenty years ago, families later took advantage of the kumquat fruits to make drinks, jams and spices. Yet, since the economic incentives that drive today’s vendors and gardeners to apply speed fertilisers and other chemicals to stimulate fruit production and slow ripening, people hardly ever keep the kumquat tree, even though it constitutes an ongoing living entity. That said, when it continues to live in the tree holes, it reinvigorates and becomes a living presence again, repudiating its treatment as a disposable product – as something deemed convenient and timesaving in the ebbs and flows of the capital city (Figure 10).

Without the intervention of urban forces, local plants germinate on their own, attesting to their enduring and lasting survival. In one hole, a cây dướng (paper mulberry tree – a local and pioneering species) has been growing for six months in a decent state. In other holes, cỏ gà (scutch grass), cỏ voi (elephant grass), cỏ lá tre (carpet grass) and chua me (wood sorrel) thrive. I am invited to nibble on the wood sorrel’s leaves, to sit down and look for which part of the scutch grass can be made into a toy. Unlike the ones neatly cultivated on Láng Hạ street whose names are unknown to the local people, these wild grass species are remembered by them and registered in the local collective memory. Memories of the land henceforth are located in trivial species usually deemed undesirable in the urban landscape (Figures 11 & 12).

The tree holes also share the space with more mobile agents on the pavement – the street vendors, motorbike taxi drivers, manual labourers or the homeless people who similarly fall short of civilised urban ideals (Figure 13). Although subject to and compromised by urban management and clearance campaigns, they still carry on their livelihood and formulate their own cultures. These activities nurture aspects of city life, many of which stem from earlier modes of living in this land before they were partially curtailed by urban standards. The contradictions embedded in this specific geography and history of Hanoi render the pavement an ambiguous terrain emerging from human-nature interaction. Among strictly controlled landscapes, these terrains invite the imagination to roam beyond a modern cityscape and outwards towards a projection of a distant village. On Thuỵ Khuê street, a cây lộc vừng (freshwater mangrove tree) grows on a fallen dâu da xoan (Chinaberry tree) (Figure 14). On Trần Nhật Duật street, a series of tree holes breathe quietly between the manicured gardens.

Finale: Durational Staging and a Pending Future

What takes place in the tree holes is not uncommon in the city. Rather, in one form or another, this phenomenon has been recurring for the past 30 years, pertaining to various urban management schemes. Yet, the tree holes present themselves as powerful spontaneous stages through which the city’s dynamic landscape and its multiple layers of meaning-making and temporalities are revealed.

On this stage, each tree hole formulates its own landscape. Together, they form a cluster of disparate yet co-emerging micro-landscapes in entanglement with organic human interactions. It is in this ambiguous terrain, devoid of top-down management and rich in bottom-up life routines from the pavement, that the trees and plants can fulfill a life cycle of being born, growing and dying. Then they partake in the city rhythm and speak to the area wherein they are located. They become part of the landscape, rather than existing as a nostalgic reminiscence or a lost, alienated piece of land. They can retain or let go of attachments to an agricultural village life or to a concrete pavement, to embody new forms of existence. In their full potential, they generate other entities in mutual response to urban and natural ones.

This stage of the tree holes may be of limited duration, and it will cease to exist once the authorities issue a new plan that reclaims them. Then the holes will be returned to a controlled state, home-grown species will be uprooted again to be replaced by urban, often colonial, ones, leaving no space for wild grass and plants to thrive. Still, the future remains unforeseeable. At this moment, no one knows whether or not a filled hole will be excavated to replant a new tree, or whether or not a recently planted tree will grow strong enough to deter the authorities from sutting it down. At this moment, the performative stage continues.

Conclusion

This paper prompts us to think of the tree hole as an unexpected phenomenon emerging from a natural disaster — one that exists in a suspended state, enclosed within multiple temporal and spatial conditions. Given the rigorous urban management of Hanoi, the tree hole presents an intriguing field of observation, opening a vast horizon of urban voids as both a site of respite and a stage for performing the city’s past and present.

By attending to the performativity of these tree holes, the paper embraces the ephemeral and marginal nature of the urban void rather than projecting expectations of what it should become. This stage is a fleeting occurrence when compared to the ingrained colonial structures and practices of urban management that have persisted for more than a century. Attempting to encapsulate and define the tree holes is only slightly different from the work of urban planners — although here, I consider myself as attuned to these urban dynamics.

It thus approaches the tree hole as a transient archive of loss, resilience, and unfinished urban memory.

Photo appendix

Nguyen Vu Hai

Nguyen Vu Hai is a cultural activist based in Hanoi, Vietnam. His work examines the intersections of urban ecology, civic participation, and environmental governance within rapidly transforming urban contexts. He has been actively involved in grassroots initiatives such as The Trees Movement and in collaborative research exploring sustainable and community-driven urban futures.

Hue Nguyen

Hue Nguyen is a researcher, writer, and emerging curator based in Hanoi and Taipei. Her work explores contemporary Southeast Asian art, cultural translation, and post-socialist visual cultures, with recent participation in Para Site’s Workshops for Emerging Arts Professionals 2024: New Flows in Hong Kong.