Part 1. A Socially Collaborative Art Project: Song of the Wind (2022–2025)

Song of the Wind began in 2022 in Yaksan-myeon, a coastal township in Wando, South Korea and by 2025 had expanded to Hanoi, Northern Vietnam, the riverine neighbourhoods along the Pasig River in Manila and the estuarine and coastal zones of Hsinchu, Taiwan – encompassing Jiugang Island near the mouth of the Touqian River and Naluwan Street, where Hongshuigang Creek meets the sea. Yet this project did not unfold along a linear geographic trajectory, but as a fluid movement attuned to the rhythms, memories and sensory experiences that emerge at the edges of place. Part 1 of this article reflects on the foundational phase of Song of the Wind in Korea. Part 2 examines how those concerns expanded into a multi-sited framework, revealing more intricate layers of temporality and the socio-ecological conditions unique to each site. Part 3 turns to the ethical, aesthetic, and curatorial implications of these incomplete and dissonant rhythms, offering theoretical and methodological reflections that propose an expanded framework for transnational collaboration.

Amidst socio-structural transformations – marked by post-industrial decline, climate change, migrant labour, legacies of colonialism and uneven urban development – Song of the Wind engages with the rhythms, affects and power dynamics that shape communities and ecologies. Drawing on Henri Lefebvre’s concept of rhythmanalysis (2004), the project investigates the political and sensorial conditions of spatial production. It simultaneously traces the entangled agencies of human and more-than-human actors, resonating with Donna Haraway’s call to stay with the trouble of living on a damaged planet (2016)1 and Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory (2005), which emphasises that human and nonhuman entities are bound together in affective networks of interaction. Here, space is not a neutral container but a generative field of socio-ecological tensions – one in which artistic practice becomes a form of attunement to what Deborah Bird Rose (2017) describes as the ‘shimmer’ of co-presence: an ephemeral yet ethical recognition of shared vulnerability and interdependence.

Rather than assigning artists to merely decorate specific sites, the project reimagines public art as a critical and relational practice. Art is approached not as a finished product but as a situated intervention within the complex ecological and lived realities of place. The entire process is designed to serve as a site of questions, dialogue and co-emergence.

While engaging critically with the limitations of relational aesthetics as theorised by Nicolas Bourriaud (2002) – particularly its tendency to aestheticise social interaction while overlooking structural inequalities2 – the project draws on Grant Kester’s dialogical aesthetics (2004), Karen Barad (2007) and Jane Bennett’s (2010) new materialism and Homi Bhabha’s concept of Third Space (1994) to reconceptualise public art as a field of negotiation where aesthetics, ethics and ecology intersect.

Bhabha writes in The Location of Culture that the Third Space is ‘a place of enunciation where new meaning and strategies are elaborated’ (1994: 36) and is, therefore, a discursive site of hybridity, translation and liminality. Song of the Wind adopts this concept to suggest that public art may operate not merely within physical space, but through a performative process across cultural difference, affective translation and relational risk.

This approach foregrounds the indeterminate encounters and tensions between artists and communities, humans and nonhumans, localities and transnational flows – suggesting that ethical responsiveness and multi-positional negotiation are fundamental to collaborative art-making. Nonetheless, Bhabha’s framework may risk abstracting the material and ecological specificities of place or downplaying structural power imbalances, thus requiring critical reflexivity (Oh 2021: 77– 85).

Song of the Wind acknowledges such pitfalls by grounding its practice in the sensory and socio-ecological particularities of each context. Through what I call ‘responsive relationality’, the project seeks to generate new rhythms for collective action, attunement and shared world-making.

1.1. Situated Agency: Artists, Migrant Labour and Curatorial Ethics in Wando

Building on this conceptual grounding, I will now examine the curatorial strategies and ethical frameworks that shaped the initial phase of Song of the Wind (Yaksan-myeon, 2022–2023) as a socially engaged art project. Framed by the notion of situated agency,3 this section explores how artistic practice can serve as an ethical and relational intervention – mediating between migrant labour, local communities and curatorial intent within a rapidly ageing, post-industrial fishing village.

Rather than evaluating socially engaged art through outcomes alone, I foreground the temporal, affective and political negotiations that emerge through context-specific processes. I begin by examining the international artist recruitment process by open call, which was conceived not as a procedural necessity but as a curatorial method that centres autonomy, voluntariness and ethical self-positioning. This approach was grounded in a critique of instrumental models of participation, drawing instead on dialogical and responsive frameworks.

Attention then turns to examining how collaborative structures were designed and implemented, seeking to balance artistic authorship with the lived experiences of villagers – particularly elderly women and migrant workers – whose perspectives were frequently marginalised within dominant cultural and institutional discourses.

Case studies, such as the renovation of a disused village hall and a series of community-led mural projects, illustrate how site-specific interventions can reconfigure public space, redistribute voice and disrupt normative hierarchies embedded in rural cultural policy. These interventions are not understood as static outcomes, but as ongoing acts of attunement – to place, memory, labour and ecological temporality.

In addition to Kester, I also draw on theoretical insights from Claire Bishop (2012) and Miwon Kwon (2002) to discuss how Song of the Wind is situated within broader debates on dialogical aesthetics, participatory ethics and the politics of place-making. Ultimately, it is argued that socially collaborative art must be understood through the dynamic interplay of context, agency and relational ethics – particularly in peripheral and structurally precarious environments.

1.2. Artist Recruitment and Structure of Participation

Image © Song of the Wind Project.

For the first iteration of Song of the Wind in Yaksan-myeon, only a small number of artists were directly invited to participate; these were all individuals who had previously shown interest in my curatorial practice, and they joined the project after carefully considering its aims. The decision to also recruit artist participants through an international open call stemmed from a curatorial belief that artists should engage actively, thoughtfully and voluntarily with the project’s curatorial vision and the socio-ecological realities of the project’s site.

Thus, the open call functioned as a curatorial strategy to foster ethical commitment from the outset; yet behind each artist’s voluntary engagement lay divergent desires and expectations shaped by personal trajectories.

To ensure both fairness and curatorial depth, I invited Frances Rudgard (Mekong Cultural Hub), Indonesian architect and activist Marco Kusumawijaya and British curator-educator Tessa Peters to serve on the international jury. Their participation reflected a conscious departure from conventional selection criteria. Rather than prioritising institutional prestige or artistic reputation, the jury focused on identifying artists with the sensitivity, disposition and ethical orientation necessary for site-responsive and socially engaged practice.

Artists selected through this process were required to undertake residencies of between one and three months in Yaksan-myeon, immersing themselves in the community. This structure marked a clear departure from event-based public art models, where artists typically engage through short site visits, submit proposals remotely and delegate fabrication. In contrast, Song of the Wind prioritised direct presence and sustained engagement, encouraging participants to respond to the site’s social and historical specificities through lived experience.

Of course, even a month-long stay could not fully encompass the complexity of the place. To address this, I conducted regular field visits for a year prior to launching the open call. This initial research was not merely about collecting data; it aimed to build trust and to lay the ethical groundwork for collaboration.

1.3. Structure and Execution of Collaboration

Image © Song of the Wind Project.

As previously outlined, the collaborative structure of Song of the Wind was designed to embody the project’s core values. Rather than adhering to predefined hierarchies or fixed roles, the project cultivated a fluid and responsive mode of working – one that could accommodate the desired goals of asymmetry, difference and the possibility of mutual transformation (cf. Bishop 2012: 12–19).

The collaboration unfolded through three interrelated pillars: site-based research residencies, co-creation through everyday engagement and a consultative framework for implementation.

During the period of residency, participating artists engaged with the local environment and informal, everyday exchanges with village residents. This repositioned the artist not as an external expert or cultural producer, but as a co-explorer attuned to the lived rhythms, textures and temporalities of place. Residency time was not merely preparatory; it was integral to the formation of situated relationships and the grounding of artistic intent.

Second, co-creation practices were developed through sensorial modes of engagement rooted in the everyday lives of residents. In one project involving the reuse of an abandoned village hall, middle-aged women from the community were invited to shape the spatial atmosphere. Together, we tended the plants growing in a small vegetable garden, discussed what else could be planted, implemented those ideas and used food waste from the artists’ stay as compost. Rather than formal workshops, these interactions emerged through everyday conversations while passing through the neighbourhood, creating informal yet meaningful encounters between insiders and outsiders. The artistic process focused not on producing visual outcomes, but on building relational bonds that were later rearticulated through subtle aesthetic and spatial gestures, such as the collective arrangement of plants, the placement of seating areas and minor alterations to the hall’s interior that reflected input from residents.

Third, the implementation phase was grounded in an ongoing consultative process among artists, residents, the curator (myself as the author of this paper), and local collaborators. All the artworks were realised in partnership with local technicians and community members – not as a form of outsourcing, but as a generative and collectively held moment of making. Execution was understood as time and space for cultivating trust, responsiveness and co-agency, rather than as a means to fulfil predefined deliverables.

Taken together, this structure marked a deliberate departure from event-driven exhibition formats. Collaboration was not treated as a means to an end, but as an open-ended process – a field of situated negotiation and embodied attunement (Oh 2021: 116–123). It was within this processual space that the ethical and imaginative potential of socially engaged art could unfold, aligning with Butler’s claim that our vulnerability to one another constitutes the very condition of ethical responsibility (2004: 134).

1.4. Theoretical Approaches to Publicness and Place-Based Practice

Before launching the international open call for participating artists, I initiated a research-based collaboration with the Innovative Design Education and Research Group on Idle Spaces in Declining Cities at Pusan National University.4 This partnership was not only pragmatic but also guided by ethical and theoretical motivations. Most notably, through a memorandum of understanding with the Jeonnam Cultural Foundation, this project proposed an experimental model of inter-regional collaboration – bridging the fragmented infrastructures of Jeollanam-do in southwest Korea and Gyeongsangnam-do in southeast Korea, these being the provinces within which Yaksan-myeon and Busan are respectively located.5 In a cultural landscape where such alliances are rare, this constituted an attempt to traverse administrative and cultural boundaries through dialogical and practice-led engagement.

Despite efforts to work with Jeonnam-based institutions, entrenched social networks and localised power structures made long-term collaboration difficult. Even though I was formally introduced to Wando through the cultural foundation, I remained an outsider, perceived as both institutionally external and socially peripheral. As Judith Butler reminds us in Precarious Life, relationality emerges under conditions of vulnerability and misrecognition (2004: 19–21). My positionality in the project – simultaneously connected and excluded – was defined by the precarity of intersubjective relations, requiring a curatorial orientation grounded in responsiveness rather than authority.

These dynamics also recall Chantal Mouffe’s notion of the agonistic public sphere (2000: 80–89). As Claire Bishop (2012) has argued, community-based art often masks conflict with the language of harmony. Yet, if the public is inherently fractured, collaboration must be understood not as consensus-building, but as a provisional space of negotiation, friction and dissensus. This approach also resonates with Held’s (2006) argument that democratic models must be continually redefined in response to changing social and institutional contexts – suggesting that collaborative art practices, too, require adaptive forms of participation and shared decision-making within evolving public spheres. Miwon Kwon similarly contends that site-specific art cannot be reduced to its geographical locus; rather, it must attend to the discursive and institutional processes that constitute place (2002: 3–5, 26). In this light, the outsider’s gaze does not assert superiority but serves as a form of defamiliarisation – revealing the situatedness and complexity of what is often taken for granted by insiders.

The collaboration with the Pusan National University research group functioned not only as logistical support but also as a performative structure of inquiry. It enacted, in practice, the ethical tensions and power dynamics that underpin socially collaborative art. This particular dialogical collaboration operated not through consensus but through affective listening, sustained conversation and negotiated conflict (Kester, 2011: 7–11).

As Lefebvre argues in The Production of Space, spatial practices are always socially and ideologically produced (1991: 26–30). Song of the Wind treated publicness not as a neutral setting, but as a contested and constructed field, a space where artistic interventions could unfold as relational practices that reconstruct social ties and open new horizons of collaborative imagination.

1.5. International Residency and the Renovation of the Former Village Hall

Video 1: Renovation of the old village hall in Dangmok-ri, which served as accommodation for the international artists-in-residence of the Song of the Wind project (2022–2023); it has since been used as a community gathering place for middle-aged residents. Video documentation by Jaehoon Choi. Video © Song of the Wind Project.

The theoretical and structural considerations I have outlined were made manifest through specific spatial and relational interventions. A particularly significant example was the transformation of a disused village hall in Dangmok-ri into an artist residency house, an intervention that reconfigured the built environment while reanimating its social significance.

Professor Woo Shin-Koo of the Department of Architecture at Pusan National University participated in the Song of the Wind project as a research collaborator. The partnership with his BK21FOUR Research and Education Program for Living SOC Innovative Design Using Empty Spaces in Declining Cities facilitated an extended spatial investigation into the idle and transitional sites of Haedong-ri and Eodu-ri in Yaksan-myeon.

At the initial stage of converting the village hall into a combined living and working environment for participating artists, Professor Woo and I jointly proposed the involvement of Ian Architecture and furniture designer Kim Byungseok, both based in Busan. Working in close coordination with a local construction office led by a long-term resident builder, Ian Architecture executed the renovation while negotiating the practical and ethical conditions of collaboration within a rural context. Throughout this process, the Ian Architecture team cultivated relationships grounded in mutual learning, situated knowledge exchange and respect for local expertise.

The tenor of this collaboration was memorably captured in a villager’s gently humorous remark: ‘Why bring architects all the way from Busan when Wando has its own?’

This utterance signalled the emergence of a cautious yet productive dialogue between external practitioners and the local community, foregrounding the negotiation of expertise, locality and authorship within socially engaged architectural practice.

Once the renovation was completed, basic appliances and kitchenware were added to ensure the space’s functionality as a temporary home. Importantly, establishing a material and symbolic continuity between the artistic intervention and local social needs is crucial for ensuring contextual relevance. The space, while intended as a temporary residence for artists, was always conceptualised as part of a reciprocal and cyclical process of spatial use, care and return.

Dangmok-ri already had a newly constructed, large-scale community hall, which was primarily used by the senior citizens’ association for regular meetings. In contrast, the former village hall had gradually become peripheral. Its first floor was occasionally used by a women’s association composed mainly of middle-aged residents, although use was irregular due to villagers’ demanding schedules tied to fishing. The space was typically accessed only in the off-season – during winter or high summer, when fishing paused. The second floor housed a billiards table used by the village’s ‘youth group’, although the space was rarely visited outside of major holidays. Notably, the so-called youth group was in fact composed mostly of men in their forties or older – a telling disjunction between official naming and demographic reality, reflective of the structural ageing and depopulation facing many rural island communities in South Korea.

This context underscored the importance of treating idle spaces not as empty containers, but as relational sites whose meaning, use and symbolic function evolve. As Lefebvre reminds us, public space is never neutral – it is produced, encoded and often rendered obsolete or invisible through shifting power relations (1991: 68–77). The renovation of the former village hall was thus not merely a technical or aesthetic upgrade. It was an invitation to reorient oneself toward the rhythms, stories and marginalised infrastructures of the village.

From a curatorial perspective, this intervention functioned as a sensorial and relational experiment: a form of attunement through shared space, in which artists, architects and residents came together not to impose new functions, but to explore the afterlives and latent affordances of an ageing site. In doing so, the project positioned public art not as a spectacle or symbolic monument, but as a mode of everyday cohabitation and ethical neighbourliness – emerging through care and use.

1.6. The Colour Mural: Collaboration between Artist Soo-Kyung Lee and the Village Mothers’ Group

Artist Soo-Kyung Lee is not typically associated with socially engaged or community-based practice. Grounded in studio-based painting and sculpture, her career has centred on the material and compositional sensibilities of colour. Based in Paris, she has long explored the affective qualities of chromatic relationships. Her participation in Song of the Windmarked a significant and generative shift in her practice – an expansion of painting into the realm of collaborative, site-sensitive engagement.

In 2022, Lee undertook a site-specific mural project on Yaksan Island in collaboration with a local mothers’ group composed of middle-aged and elderly women. The work emerged through an open-ended process of sensory exploration and shared composition, in which colour became both medium and method. Through ongoing conversations with villagers, Lee gathered affective impressions and recollections of the island’s seasonal tones – sunlight filtered through trees, the blue-grey shimmer of tidal waters, the dust of unpaved roads and the warmth of shared meals. These perceptual fragments were translated into an abstract mural painted on the façade of an old storage building.

What began as a visual intervention ultimately became a collaborative process wherein painting operated not as private authorship but as collective sensory calibration. The work offered a compelling challenge to dominant conventions of rural muralism in Korea, where public art is often expected to depict legible motifs such as abalone, fish, flowers or other emblems of place.6

In contrast, the Colour Mural subverted such conventions. The collaboration focused not on representation, but on embodied processes of choosing, mixing and arranging colours. Lee led a series of hands-on workshops where activities created a space for the exercise of aesthetic agency by residents who had rarely engaged in such experimentation.

This participatory process did not hinge on achieving consensus or producing a coherent visual language. Rather, it unfolded through gestures, rhythms, hesitation and resonance that can be recognised as a form of Kester’s dialogical aesthetics: art-making grounded in mutual recognition, relational labour and affective exchange (2011: 9–33). In this context, aesthetic learning occurred not through instruction, but through shared intuition.

The project invites us to reconsider the possibilities of ‘inclusive art’, not as an instrumental or didactic category, but as a contingent field of co-presence and slow transformation. Soo-Kyung Lee’s mural became a threshold: between studio and street, between private memory and shared surface, between art and life. It illustrates how even artists not typically engaged in community practice can participate in the co-creation of new visual vocabularies, rooted in site, relation and the ethical imperative to listen.

1.7. Ethics of Co-Creation: A Mural Project with Young Artists and Eodu-ri Residents

This section examines the ethical and structural dynamics of co-creation through two mural projects carried out in 2022–2023, one of which is the Colour Mural discussed above. Both projects engaged local communities through sensory and collaborative processes, yet they also revealed persistent tensions surrounding authorship, labour and institutional responsibility. By situating these tensions within the broader field of socially engaged art, the section reflects on how co-creation operates not only as a generative practice but also as a site of unresolved ethical and institutional dilemmas such as fair recognition, equitable labour and sustainable support structures.

Inclusive Colour Work: Soo-Kyung Lee in Dangmok-ri

As already explained, for the mural sited in Dangmok-ri, led by Soo-Kyung Lee, the artist used colour as a medium for dialogical exchange with a local mothers’ group, and through informal conversations and hands-on workshops, participants explored palettes inspired by Wando’s natural and emotional landscapes.

Lee’s approach embodied inclusive art practice grounded in mutual trust, exchange and non-hierarchical collaboration. The project emphasised shared rhythms of attention rather than visual output, allowing participants to shape the spatial atmosphere through their collective presence.

Later, members of the mothers’ group applied what they had learned to a new mural elsewhere. While this continuation was encouraging, the results also highlighted limitations: colours were often used repetitively, and creative authorship remained constrained. Nevertheless, the groundwork for aesthetic literacy and collaborative authorship had been laid – an important first step toward more independent and imaginative local practices, albeit within the limits of minimal institutional support.

Critical Reflections in Eodu-ri

In contrast, the second mural project – realised in Eodu-ri with a group of artists and residents – brought forth critical reflections on authorship and labour. Initiated for the only two children living in the area, the project emerged from workshops that translated their drawings into a mural design. The process unfolded over a series of summer afternoons, involving intergenerational exchanges between children, residents and emerging artists, and can be understood as an instance of relational art in which the artwork itself facilitated encounters among people.

Beneath this surface of affective co-creation, however, complex ethical questions surfaced. Many of the young artists involved were students or mentees of senior artists formally invited to the project. While the initiative was presented as a space for collaboration and skill-sharing, the structural reality often mirrored exploitative dynamics: younger artists contributed significant labour without formal credit or compensation. These arrangements, frequently framed as educational mentorships, revealed how public art projects can unwittingly reproduce entrenched hierarchies and obscure the professional standing of emerging practitioners.

Both mural projects reflect a broader issue within local cultural policy in Korea, where public art in rural areas is frequently regarded as community service or amateur activity. Local cultural foundations often provide small stipends to hobbyist artists while expecting professionals to contribute their labour voluntarily under the guise of ‘giving back’. Such frameworks blur the line between amateur and professional art, eroding recognition of artistic labour as skilled and remunerative work.

Furthermore, when established artists enlist younger collaborators without ensuring equitable credit or compensation, the ethos of co-creation is compromised. What appears as collaborative authorship may, in fact, reproduce asymmetrical power relations – undermining the very ideals of socially engaged practice. As Bishop (2012) and Kester (2011) remind us, participation is never ideologically neutral; it is a site of negotiation, conflict and political tension.

Despite these structural constraints, the Eodu-ri project also catalysed internal conversations among participants regarding ethical authorship and visibility. Young artists actively questioned their roles, and efforts were made to establish greater transparency in decision-making and crediting. Yet such attempts remained circumscribed by the broader funding system, which lacks institutional mechanisms for protecting emerging artists’ rights.

Toward Ethical Models of Co-Creation

To move toward more ethical models of co-creation, local cultural policy would do well to establish support structures that distinguish between amateur and professional practices; this would help to ensure fair compensation and promote sustainable working conditions. Possible approaches include dual-track project systems – where separate frameworks support both community-driven initiatives and professional artistic practices – and phased engagement models that provide step-by-step commitments for participants.

Unlike state-led or museum-driven public art programmes that often instrumentalise participation to fulfil policy goals, Song of the Wind sought to foster genuinely relational forms of engagement. Its political dimension did not lie in advocacy or antagonism, but in an ethical commitment to creating conditions where participants could self-organise, co-sense, and at times, reach forms of consensus with others and sustain their practices beyond the project’s temporal frame. Within this framework, the curator’s role was not to manage or direct but to act as a mediator of relations,7 temporalities,8 and situated orientations9—holding space for divergence, trust-building, and mutual learning.

This curatorial position aligns with Bruno Latour’s conception of the social as a continuously reassembled network of heterogeneous actors (1993: 1–5). Collaboration here becomes a means to explore how voice, visibility, and agency can be reconfigured within evolving ecologies of relation. Rather than striving for unity or representational coherence, the project encouraged asymmetrical encounters, productive misunderstandings, and shared questions across difference.

Part 2. Attuning to Socio-Ecological Rhythms: Sensory Ethics and Transnational Place-Based Practice

Building upon the curatorial ethics and locally embedded structures developed in the 2022–2023 Wando project – which emphasised long-term relationship-building and ethical foundations through place-based artistic practice – Part 2 explores how those concerns were expanded into a multi-sited framework. Such expansion revealed more intricate layers of temporal dynamics and socio-ecological conditions specific to each site.

The site-based collaborative approaches, led by participating artists and designed to engage members of local communities, unfolded through dialogues, workshops and artistic practices across the northern coastal villages of Vietnam, Hanoi, Manila in the Philippines and Hsinchu in Taiwan. These collaborations functioned within an experimental curatorial field – a space that does not pre-exist but comes into being through our collective making. Rather than serving as preparatory stages for artistic production, they operated as political and ethical spaces in which the terms of collaboration could be tested, sensed and negotiated.

Echoing Kester’s notion of dialogical aesthetics as a process of contextual negotiation rather than consensus (Kester 2011), the following sections examine how these curatorial principles were enacted across different sites – beginning with the Manila phase, followed by Hanoi and Hsinchu – each revealing distinct socio-ecological rhythms and ethical conditions of collaboration.

2.1. Manila, Philippines: Artistic Practices for Listening to the Rhythms of the Pasig River

In Manila, sound-based field research was conducted along the Pasig River. The project did not approach the river merely as a geographic backdrop or ecological resource, but as an affective space where colonialism, development, silence, resistance, memory and survival intersect. Its aim was to perceive place through layered rhythms and affects, and to employ sensory-based artistic practice to render visible the urban power structures and social inequalities embedded in the environment (cf. Jackson 2011: 14–25).

The research drew on Lefebvre’s (2004) concept of rhythmanalysis to explore the social rhythms inherent to place and to experiment with how artistic practice might sensorially attune to and capture them. For Lefebvre, rhythm is not mere repetition but a pattern of tension and harmony formed through the interrelation of space and time, life and technology, matter and power. This project extended his theory through auditory exploration, drawing on Salomé Voegelin’s notion of auditory epistemology (2014) to recover marginalised layers of silence and peripherality – dimensions often excluded from visually centred systems of urban knowledge. It further examined how sound might mediate new relations across these fragmented terrains.

Fieldwork was carried out in collaboration with residents, NGO activists and young artists, tracing multiple routes – on foot, by boat and through stops at docks and markets. Along these routes, the research encountered diverse riverside living environments and everyday scenes: multilayered residential settings of local communities, crowds gathered at churches, the bustle of local markets and the imposing presence of the Philippine presidential palace overlooking the river. The ambient sounds gathered along the way, together with retrospective interviews, were crucial for sensing and narrating the rhythms of the Pasig River. Pausing to converse with residents during walks was not simply a method of sound collection but also a performative device for reconstructing memory and cultivating a shared sense of place. The project showed that affective interaction through sensation can function as a critical artistic practice for recalibrating spatial politics and responsiveness.

Despite the river’s physical barriers – pollution, embankments and elevated highways – the research revealed that the Pasig River continues to serve as an emotional conduit for communities. Its residual sonic traces carry the potential to reassemble temporally and spatially fragmented individuals into what LaBelle (2010) describes as an ‘auditory community’. In this sense, the project advanced an integrated framework at the intersection of aesthetics, sociology and critical urban research, where city, ecology, society and sensation converge.

Prior to Song of the Wind in Manila, however, my collaboration with 98B Collaboratory – an independent arts platform in the city – revealed a different set of expectations. Instead of receiving a formal letter of invitation, I was sent an invoice detailing charges for accommodation, local coordination, project management, transportation and meals. The lack of clarity about the accommodation, the roles of proposed coordinators or managers and the actual forms of collaboration raised questions about the legitimacy of these costs. The total sum was also considerable, contrasting sharply with the more supportive arrangements I had encountered with partner institutions in other countries.

Although I expressed a willingness to contribute financially, I stressed that such resources should sustain a spirit of mutual artistic collaboration rather than frame the relationship as a service transaction. In hindsight, this episode underscored a disconnect between my understanding of collaborative research and the institutional logic within which 98B operated. More broadly, it revealed divergent assumptions about relational practice – especially in how responsibility, reciprocity and shared authorship are defined and enacted in transnational artistic collaborations.

During my stay, my focus shifted to researching activist practices related to socio-ecological issues in the Philippines. I facilitated two workshops with 98B members: Cultivating Edible Landscapes and Weaving the Threads of Connection. I paid for accommodation and stayed at the private home of a 98B member, which, though not an official guesthouse, functioned as a space for visiting artists supported by grants from institutions such as the British Council and Japan Foundation.

While this setup might appear to promote shared resources, it also revealed how public funds are absorbed into informal, unregulated spaces – transforming institutional assets into cultural capital. The lines between hospitality and service, public and private, became blurred. Support, labour and goodwill were entangled, raising questions about ‘who invites whom?’ and ‘what constitutes the public or private domain in collaborative cultural contexts?’ This case laid bare the asymmetrical expectations and imbalanced power dynamics that are often overlooked in Global South collaborations.

Rather than being valued as equal partners, cultural hospitality frequently reduces local artists to the role of hosts or fixers, burdened with unacknowledged labour and responsibility without compensation. In such settings, artists are not merely guides – they carry the weight of daily care, logistical negotiation and invisible forms of labour that sustain projects but remain unacknowledged. Ensuring ethical and autonomous artistic collaboration requires a wider critical reflection on these conditions and the development of new frameworks based on explicit agreements and fair cooperation.

In seeking to prioritise ethical considerations, it was important to clearly define my relationship with 98B. I asked the sound artist, Frankie, who had accompanied me during my stay in Manila, to conduct the remaining research after my departure, and I renegotiated with the 98B team the allocation of the expenses I had already paid. I ultimately absorbed the extra costs myself. My decision to involve Frankie was not simply to compensate her for accompanying me, but because she had shown genuine interest in my research theme, and there was potential for meaningful connections with her own artistic practice. I hoped that this arrangement would help her further develop her work as well. Since our final exchange in April 2025, I have continued to reflect on the continuity and preservation of the Pasig River recordings – whether they are being archived, sustained and kept accessible for future use – and I await with anticipation how these early traces of research might eventually be taken up in subsequent exhibitions or further collaborative work.

Through this process, I hoped the Pasig River could become a resonant conduit in which place-based memory and relational labour were not only documented but reassembled through listening. Such a practice, in turn, opened the possibility of reframing collaboration as a politics of sensing – foregrounding auditory perception as a mode of ecological and social critique. At the same time, however, I remained uncertain whether Frankie would be able to continue developing this work independently over the long term.

2.2. Hanoi, Vietnam: Exploring the Micropolitics of Urban Trees and Memory

The Hanoi workshop served as a foundational step in the development of the Narrative Archive of Trees, a project that explored the social and affective significance of trees within urban ecosystems.10 Building on this initiative, the research involved site-specific experiments in responsiveness through collaborations with artists, botanists, citizen activists and spiritual intermediaries who care for sacred tree altars. This approach resists reducing nature to a mere backdrop or resource, instead proposing a sensorial and ethical mode of practice aimed at restoring interaction with non-human beings (Myers 2017).

One of the most striking findings during the research process was that many of Hanoi’s prominent street trees had been planted during the French colonial period and consisted predominantly of exotic tropical species imported from Africa. These trees, envisioned as part of a colonial urban landscaping project, went on to shape the aesthetic norms of Vietnamese city planning for decades to come. However, they proved ill-suited to Hanoi’s narrow, concretised pavements and inadequate drainage systems, and their root structures often failed to take hold. When Typhoon Yagi struck Hanoi in September 2024, thousands of these trees toppled – an event that laid bare the ecological limitations of state-led, functionalist landscaping policies (Hải 2016).

This historical and ecological context produced a peripheral narrative that unsettled the standardised order of modern urban planning, particularly concerning public landscaping.

Within the Song of the Wind project, both the Ground Conversations and Participatory Practice Workshops at the Temple of Literature in Hanoi critically re-examined the colonial legacy of urban planting, aiming to reconfigure human–tree relations through narrative modes of engagement.11 Participants moved beyond conventional forms of visual documentation and archiving, instead transforming stories, memories, prayers and care practices – as well as experiences of loss and recovery – into an aural and affective method of narrative botanical mapping (Voegelin 2010).

This practice constituted an aesthetic and epistemological challenge to dominant urban memory structures, especially the visually centred systems of urban archiving. It also offered an alternative mode of assembling community narratives through attuned memory, aiming to reimagine human–non-human–place relationships and to experiment with new sensorial-political sensitivities in urban ecological transition. In this sense, the project resonates with the more-than-human in theory and art foregrounding forms of coexistence and ecological imagination that move beyond anthropocentric frameworks (Tsing 2015; Haraway 2016).

Parallel to this, a smaller workshop involved planting two trees in the Văn Miếu (Temple of Literature), a prominent cultural heritage site in central Hanoi. This gathering attracted spontaneous participation from local visitors and city dwellers, demonstrating how acts of planting in public space could serve not only ecological, but also symbolic and cultural functions. The Temple, located at the intersection of traditional Confucian values and contemporary Vietnamese cultural politics, provided a powerful discursive setting.

Importantly, the workshop included an educational component that emphasised how to plant in ways that support healthy tree growth – such as maintaining distance between saplings to ensure adequate sunlight and to prevent competition. These practical considerations foregrounded a mode of care that was both ecological and ethical.

In collaboration with Think Playgrounds, the Socially Engaged Practice: Planting Project at the Red Riverbank was developed as part of a long-term initiative with residents of the riverside Hong Ha Ward (formerly part of Hoan Kiem District). The first planting took place between June and July 2025, when approximately 3,000 saplings were planted. This marked the beginning of an extended process of care and maintenance, ensuring the trees’ growth while also improving the surrounding environment. Unlike the large-scale state-led planting campaigns of the Ho Chi Minh era, this project was community-driven, aiming to revive native vegetation through sensory understanding and shared memory. In this context, planting functioned not merely as an ecological intervention but as a form of cultural negotiation, through which residents articulated their own temporalities of care, remembrance and environmental learning.12

In this context, the planting revealed not only the interplay between sensory experience and spatial symbolism, but also what Miwon Kwon identifies as the cultural frameworks and institutional discourses that condition a site (2002: 3). Rather than treating place as a fixed container, the act activated the Temple as a relational and contested site where environmental learning, cultural ritual and public participation converged. In this sense, urban ecology emerged as a field of cultural negotiation and ecological resonance.

The workshop reframed urban memory as a multispecies narrative practice, challenging anthropocentric and visually dominated archival modes. Situated responsiveness here became a method for disrupting colonial rhythms and cultivating new ecological imaginaries.

The site’s symbolic and affective resonance also attracted artists who engaged with the project in more autonomous and ephemeral ways. One such case was Korean artist Sylbee Kim, who participated in the Hanoi field trip but intentionally positioned herself outside the project’s formal structure. Rather than assuming a clearly defined role, she sought to explore how artistic research could unfold without reproducing extractive dynamics. Her reflections on the ethics of care, reciprocity and artistic labour – particularly concerning the hospitality of local communities – highlighted the moral dilemmas that can arise even in well-intentioned collaborative contexts. While not formally embedded in the project structure, her presence and practice revealed another rhythm of participation: one that foregrounds the difficulty of non-exploitative exchange and the limits of aesthetic autonomy in socially engaged settings.13

Video 2: Fieldwork journey along the Red River from Hanoi to the Gulf of Tonkin, Northern Vietnam. Video © Song of the Wind Project.

2.3. Hsinchu, Taiwan: Sensing the Invisible Rhythms and Afterglow of Jiugang Island14

In Hsinchu, Taiwan, an experimental field-based workshop titled Island of Afterglow was held on Jiugang Island, a low-lying coastal islet. The project sought to sensorially reveal the presence of this ‘semi-invisible’ island – largely absent from official maps and administrative documents – while drawing out the socio-ecological complexities and affective conditions embedded within the site. Participants engaged in multi-layered explorations through walking, sound collection and registering time as it was sensorially revealed through fluctuations of light – its shifting intensity, hues and shadows that evoked layers of local temporality, everyday life and historical presence across the island’s varied sites. These non-quantitative, responsive methodologies were used to probe not only the physical features of the island but also the affective and historical dimensions that resist capture within official cartographies.

Interviews with residents exceeded standard oral documentation: they served as micro-testimonies revealing the island’s history of administrative marginalisation, fragmented urban infrastructure and the autonomous norms of survival and governance formed within its community. These conversations illustrated how sensitively responding to site-specific rhythms could reconfigure the peripheralisation of urban space, offering a theoretical framework for alternative spatial awareness grounded in socio-ecological readings.

Island of Afterglow consisted of three sessions conducted over two days and highlighted how the socio-ecological rhythms that once marked Hsinchu’s coastal lowlands have been subjected to dual processes: erasure through state-led urban development and transformation through ecological change. The first session was held at night, unfolding as a three-part narrative situated across different areas of the island. Guided by facilitators, participants moved through these sites, engaging with shifting spatial and atmospheric conditions. Local residents, participating artists and other attendees collectively experienced a performative encounter in which stories drawn from the villagers’ lived memories intertwined with the artists’ light and sound compositions. Through this sensory assemblage, the nightscape of Jiugang Island emerged as an affective and poetic field – a site where narrative, illumination and resonance converged to attune participants to the island’s nocturnal rhythms. The second day of the workshop invited participants to encounter the island in daylight, guided by local residents who shared situated narratives of its history, ecology, and everyday life. After lunch, participants assembled at the village hall to engage in a collaborative exercise with Po-hao Chi, envisioning their own speculative versions of the island and translating these imaginative forms into digital space through 3D scanning.

Ultimately, this process resulted in a shared temporal experience mediated by sensory alignment. The act of dwelling together in rhythm emerged as an aesthetic condition for collaboration. The various workshops, held in Manila, Hanoi and Hsinchu, represented a range of experimental attempts to respond to different socio-ecological tempos through sensory-based practices. They revealed how such artistic research can perceive the lived time structures and affective density unique to each place, thereby reframing international collaboration not as a contractual or logistical exchange between institutions or artists, but as a process of creating a durational practice.15

This mode of relational calibration16 depends on the simultaneous recognition of rhythmical alignment and dissonance – of commonality and difference – and establishes ethical conditions for relationships between artists and collaborators, locals and visitors.17 As such, it invites a shift away from results-driven models of artistic collaboration toward temporally based practices of embodied presence and co-experienced attentiveness. Collaboration, in this sense, is not a predetermined task but a living process of mutual modulation,18 attuned across temporalities, spatial specificities, affective energies, bodily dispositions and atmospheric contingencies.

Rather than treating rhythm as metaphor, the Jiugang workshop approached it as an ethical mode of being-with, of coexisting alongside fragile, layered and often invisible forms of spatial life. This suggested a new paradigm of dwelling in rhythm, offering an alternative ground for socially situated collaboration.

Collectively, these preliminary experiments point to the necessity for curatorial infrastructures to be capable of sustaining long-term, situated and ethically responsive forms of international collaboration. The following section builds on this insight by examining how such experimental practices might be translated into more durable structures within institutional frameworks, with particular attention to the ethical considerations and practical challenges involved in implementing socially engaged art on an international scale.

2.4. Naluwan Street, Hsinchu, Taiwan: Rhythms of Precarity and the Ethics of Coexistence

In September 2025, I revisited Naluwan Street in Hsinchu, Taiwan, continuing the field research I had begun earlier that year. Having briefly visited the site in June, I asked the artist Fangyu, who had participated in the Jiugang Island workshop, to accompany me, knowing that communication might otherwise be difficult.

Located in southern Hsinchu, Naluwan Street is a coastal settlement, formed over forty years ago, by members of the Amis community who migrated from Taitung in eastern Taiwan to establish an informal residential area. Due to its provisional status, it embodies interwoven rhythms of precarity, care and ethical tension. These rhythms arise at the intersection between legality and belonging, manifesting as both social and sensory phenomena that shape the affective fabric of everyday life.

Facing the sea, Naluwan Street unfolds along a narrow lane built beneath towering wind turbines and protected by a seawall. Walking slowly along the lane, I spoke with residents and began to sense how their daily lives, continually reassembled through small acts of maintenance, also relied upon gestures of mutual care. On the landward side, opposite the seawall, a row of houses stands close together – each dwelling built from whatever materials were available, in response to the shifting shoreline and the contingencies of the weather. Each house carries its own improvisational narrative: residents repurpose discarded materials from nearby construction sites, share resources with neighbours and reuse whatever has been left behind. Uneven roofs, mismatched walls and layered boundaries compose a spatial language of adaptation, reflecting a collective ability to endure within circumstances of instability. These forms of construction articulate an ethics of survival grounded in reciprocity and improvisation – it is an architecture that grows from care rather than capital.

As part of a broader government initiative to support Indigenous communities in Taiwan, a mural depicting episode from the history of the Amis has been painted along the seawall at the entrance to the alley. Nearby, a sculptural streetlight portrays an Amis archer — a symbol of collective identity and pride. The recently constructed community hall, equipped with relatively modern facilities, hosts elderly residents who gather on weekday mornings and afternoons to craft small handmade items or share lunch. Together, these scenes illustrate how state support and local practices of care interweave within the rhythms of daily life.

Within the residential area, overlapping sounds – low conversations, the cyclical rhythm of waves, the rotation of wind turbines and the intermittent noise of motorcycles and passing cars – form a distinctive soundscape. At the end of the alley is a small fish market where local fisherfolk sell their catch, linking the settlement directly to the sea. Immersed in this acoustic environment, I could sense a delicate equilibrium between persistence and vulnerability.

These everyday scenes reveal how the Amis people transform precarity from a condition of despair into a rhythm of adaptation. Their lives quietly reconfigure the meaning of ‘home’, ‘legality’ and ‘belonging’, generating an emergent sense of coexistence along Hsinchu’s mutable shoreline. In this light, the rhythms of informality within Naluwan Street articulate a lived response to the uneven processes of coastal urbanisation in Hsinchu (Lai 2024).

As the land on which Naluwan remains state-owned, the settlement exists beyond the official framework of urban planning and has never received legal recognition. Figures 21 and 22 show Naluwan Street’s fragile urban condition within the shifting rhythms of sea and land, revealing how its ecological precarity mirrors its social one.

While there is insufficient justification for the government to automatically grant permanent residency or legalise such informal Indigenous settlements, from an ethical perspective, one could argue that regularising these spaces would constitute an act of restorative justice – acknowledging the historical and structural inequalities that have rendered such forms of living necessary. The spatial disparity between Taiwan’s east and west reflects the enduring legacy of colonial modernity. While the western plains developed through maritime trade routes and industrial expansion during the Japanese colonial period, the eastern region – home to many Indigenous communities – has remained economically marginalised, with limited infrastructure and employment opportunities. These uneven trajectories have compelled Indigenous populations to migrate toward the urban peripheries, where they often establish informal settlements as strategies of survival and care. As Harvey (2003) observes, the neoliberal policy of ‘accumulation by dispossession’ continually displaces vulnerable groups in the name of progress, while Sassen (2014) describes such processes as systemic ‘expulsions’. From this perspective, Indigenous informal settlements can be understood not as illegal occupations but as spatial manifestations of structural inequality and historical neglect. Field research further revealed that precarity here is not solely a socio-economic condition but also a sensory experience. Residents live in shared awareness of the sea’s shifting moods, the weathering of their homes and the uncertainty of potential displacement. Their stories, layered with memory and embodied knowledge, express an attunement to invisible rhythms that persist beyond formal visibility or institutional care.

At the same time, officially recognising this settlement as a policy precedent introduces a deeper ethical tension – potentially obligating the state to extend equivalent housing support to other Indigenous groups migrating from Taiwan’s underdeveloped east to its urbanised west (Kuan 2023). The dilemma thus lies not only within the realm of policy but also within the moral responsibility of governance: with how to reconcile administrative consistency with the ethical imperative of historical redress.

Ultimately, it compels us to ask:

Who holds the right to belong?

How do notions of publicness – and by extension, public ownership – operate in relation to those dwelling at the margins?

The Song of the Wind project thus approaches Naluwan Street not as a symbol of deprivation but as a laboratory of coexistence, where social ties and ecological rhythms are continuously recalibrated. Without romanticising marginality, the project foregrounds the agency of residents in composing shared worlds amid uncertainty. This perspective challenges the binary of legality and informality, repositioning care, adaptability and improvisation as ethical and aesthetic practices. By listening to subtle interactions among people, materials and the sea, this research highlights the importance of situated attunement in reimagining curatorial ethics across vulnerable coastal zones.

Such an attuned approach reveals that artistic intervention cannot be separated from the politics of recognition and justice. Rather, it unfolds through incomplete rhythms of negotiation between formality and informality, ethics and aesthetics, visibility and care. As Henri Lefebvre’s rhythmanalysis reminds us, these incomplete rhythms illuminate the multiple temporal registers through which informal communities sustain everyday life within structural instability.

Video 3. Footage from Naluwan district, Hsinchu, Taiwan. Video documentation by Chen Kuan-lin. Video © Song of the Wind Project

2.5. Comparative Reflection: Jiugang and Naluwan

While adopting a cultural and artistic approach to understanding Jiugang Island was not particularly difficult, engaging with the Amis community of Naluwan required caution. I could not be certain what tangible benefit an artistic encounter might bring to the residents there. As a temporary visitor from Korea, I came to realise that my most ethical gesture was not to intervene but to listen – to share food and stories, and to receive their narratives of life with care rather than with purpose.

The ethical dilemma presented by Naluwan invites a broader comparative reflection – one that considers how different sites along Hsinchu’s coast embody distinct yet interconnected rhythms of precarity and modes of response (Lefebvre 2004; Massey 2005). Although Jiugang Island and Naluwan Street are both located within the same coastal city, their spatial conditions and historical trajectories reveal divergent yet relational forms of instability and rhythm.

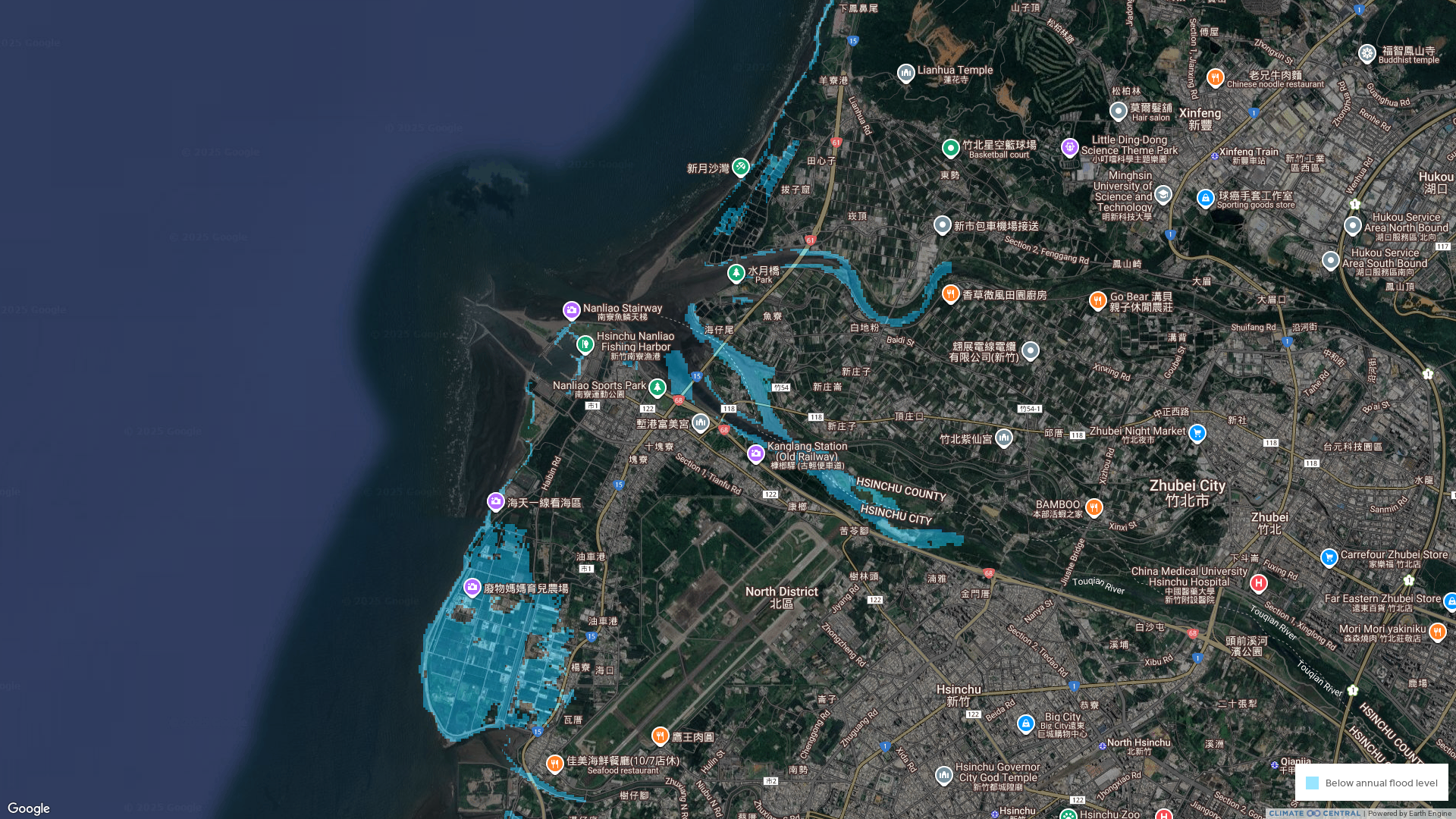

As noted earlier, recent sea-level rise projection maps suggest that parts of the Naluwan area may fall within zones of inundation risk by around 2030 (Figures 21–24). Such projections point to the community’s precarious grounding within an inherently unstable terrain. Rather than rebuilding on land already marked by the possibility of submersion, it would be more realistic – and ethically sound – to support relocation to safer ground. Yet the production of these ‘future inundation’ maps is itself a performative practice: a technoscientific gesture that renders certain futures visible while relegating others to the realm of the unthinkable (Anderson 2010; Yusoff 2018).

Map visualisation based on Climate Central’s sea-level projection model shows the southern coastal zone of Hsinchu, including the mouth of the Touqian River and Nanliao Fishing Harbour. Areas shaded in red indicate zones projected to lie below the annual flood level under the 2030 relative sea-level rise scenario (SSP3–7.0, median). While the model outlines extensive inundation along the Jiugang Island and Nanliao coastal areas, these low-lying zones are largely uninhabited reclaimed lands or wetlands rather than active residential settlements. The visualisation therefore highlights potential hydrological vulnerability rather than direct population exposure. © Climate Central, 2025.

Jiugang Island, located near the mouth of the Touqian River, is shaped by ecological tensions arising from industrial development, coastal erosion, the transformation of everyday life before and after the construction of the bridge connecting the island to the mainland, and the lingering traces of former fishing practices. Its landscape bears the afterglow of displacement, where material ruins and sedimented memories coexist within the tidal rhythm (Tsing 2015). Compared to Naluwan, Jiugang appears relatively stable in physical terms—its population is sparse, and its vulnerability to coastal erosion is dispersed across an uninhabited, semi-industrial terrain. Yet this stability is itself precarious, grounded in a landscape where the ecological processes of erosion and reclamation continually redraw the boundaries between land and water. In contrast, Naluwan Street, with its Amis population, embodies a more informal and human-centred narrative: a settlement built through acts of self-construction and endurance at the city’s southern margin. Despite their differing contexts, both sites reveal incomplete and overlapping temporalities, in which the linear time of modern urbanisation gives way to fragmented rhythms of survival and adaptation (Berlant 2011).

In Jiugang, rhythm unfolds primarily at an ecological register – through the ebb and flow of tides, seasonal transitions and the slow material decay of abandoned structures. In Naluwan, rhythm is socially and affectively constituted – emerging through collective improvisation, shared labour and the continual negotiation of dwelling within conditions of uncertainty. Together, these sites demonstrate how Taiwan’s developmental landscape records uneven temporalities at its peripheries, where industrial modernity intersects with Indigenous resilience (Escobar 2018).

Jiugang and Naluwan also share infrastructural fragilities, particularly concerning water quality and sanitation. In earlier years, residents relied on groundwater for drinking; although piped water has since been installed, its potability remains unverified. Similarly, the adequacy of the sewage system is uncertain. Such infrastructural vulnerability not only exposes everyday environmental risk but also indexes the socio-ecological precarity that defines both localities (Nixon 2011).

From a curatorial perspective, these places call for a practice grounded in responsive relationality – an ethics of attentiveness that acknowledges difference without seeking to reconcile it (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017). Engaging with Jiugang required attuning to the ecological pulse of a site scarred by industrial transformation, while Naluwan demanded sensitivity to the social and affective rhythms of a community living at the threshold of legality and recognition. In both contexts, collaboration unfolded not as consensus but as a curatorial choreography of coexistence rather than resolution (Kester 2004).

This juxtaposition demonstrates how socially engaged art projects, like Song of the Wind, navigate between visible and invisible forces—between the slow violence of ecological degradation and the intimate struggles of human precarity (Nixon 2011; Lefebvre 2004). Through field-based encounters, the project constructs a rhythmanalytic dialogue bridging environmental and social dimensions, revealing how care, vulnerability, and co-presence can operate as both aesthetic and ethical modes of practice (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017). It demonstrates how artistic practice can cultivate attentiveness to the uneven rhythms of socio-ecological life, transforming precarity itself into a space of shared reflection and relational ethics.

Curating such projects within unstable environments is less about representation than attunement – staying with the rhythms of uncertainty (Haraway 2016). The role of art, then, lies not in resolving contradictions but in inhabiting them: attentively, and with care.

Part 3. Curating Through Incompleteness: Temporal Ethics and Transnational Collaboration

Building on the multi-sited field research discussed in Parts 1 and 2, this chapter turns toward a theoretical and methodological reflection. It examines how incompleteness—as both an aesthetic and ethical condition—can function as a curatorial framework for transnational collaboration.

3.1. Theorising Incompleteness: Rhythm, Fragmentation and Relational Ethics

Drawing on the irregular and unfinished patterns observed in field-based collaborations in Wando, Manila, Hanoi and Hsinchu, I propose that these incomplete rhythms offer a lens through which to understand the temporal and ethical conditions of cross-border collaboration. Instead of seeking coherence or closure, I demonstrate how delays, interruptions and asymmetries can generate more open-ended and situated modes of working together.

While Kester (2011) underscores the importance of conversation in socially engaged art, this project suggests that genuine dialogue often unfolds through asymmetrical, nonlinear and temporally unstable relations. The incompleteness of temporal formations in Song of the Wind can also be approached through an expanded ecological lens. Haraway’s (2016) concept of staying with the trouble challenges curatorial impulses toward resolution, calling instead for a sustained entanglement with precarious life-worlds in which meaning, response, and collaboration evolve through uneven tempos—slow, tentacular, and without mastery—requiring a curatorial sensibility attuned to the flux and indeterminacy of time (pp. 1–12, 34–45).

These irregular cadences echo Glissant’s philosophy of Relation, where opacity and unpredictability are not perceived as obstacles but as preconditions for ethical co-existence (1997: 189–192).

This dynamic was vividly encountered in the informal Amis settlement of Naluwan on Hsinchu’s southern coast. Faced with precarious conditions—uncertain legal recognition, infrastructural vulnerability and the threat of land loss due to rising sea levels—the process of collaboration shifted from artistic intervention to a reflective mode of being-with. This shift further clarified that in such fragile contexts, curatorial ethics may lie not in action itself but in the sensitivity of knowing when to withhold it.

3.2. Toward a Situated Model of Transnational Collaboration

Dialogue becomes possible only through mutual openness and willingness to listen. However sincere one’s effort may be, when the other refuses to listen, exchange collapses into a monologue. To refuse to listen is to deny the very condition of dialogue. For it is through listening, more than through speaking, that we begin to move toward one another.

This understanding of dialogue forms the ethical foundation for any transnational collaboration. Within Song of the Wind, dialogue was never assumed as a given but continually reconstituted through asymmetrical encounters, cultural translation and moments of misrecognition. The expansion of the project across multiple sites revealed that collaboration cannot rely on shared intention alone; it depends on the ongoing willingness to be transformed by others. Genuine exchange requires a curatorial sensibility grounded in attentiveness and mutual responsiveness—qualities that can only emerge through listening.

The transnational expansion of the project revealed the inadequacy of universal models of curatorial practice (Kwon 2002: 29–34). Instead, a situated and pluralistic approach emerged—one shaped by local ecologies, infrastructural conditions and affective labour (Bishop 2012: 1–7).

This recognition did not signal withdrawal, but rather prompted a reconsideration of how transnational collaboration could be redefined—as a practice of maintaining attentiveness and ethical accountability across multiple sites and temporalities—and one that privileges responsiveness to local conditions while sustaining a sense of shared relationality across borders.

Three curatorial orientations anchored this model:

- Nonlinear Curation: Tim Ingold’s notion of the “temporality of the landscape” reframes space not as a container but as an active field of movement (1993: 162–70). In this project, curation unfolded through erratic temporalities—typhoon-induced delays in Hanoi, seasonal labour cycles in Wando and tidal disconnection in Jiugang, where shifting rhythms periodically isolated the island. These interruptions demanded attentiveness to situated slowness and eventful unpredictability.

- Ethical Provisionality: Claire Bishop (2012) critiques the instrumentalisation of participation in art institutions. In Song of the Wind, however, ethics was not an external standard but an emergent, negotiated condition. Trust developed through repeated co-presence, and artistic decisions were shaped by shared risk rather than consensus. This connects with Anna Tsing’s vision of collaboration without guarantees, where contingency and friction produce new social formations (2015: 1–25).

- Curating on the Edge: The chosen sites—from botanical peripheries to post-industrial islands and informal coastal settlements—were not merely geographic margins but what Doreen Massey (2005) calls thick places, dense with contested temporalities and layered histories. These edges are not only spatial but epistemic thresholds, where curatorial work must learn to be receptive to fragility rather than stability. Curating on the edge, then, is not representational but relationally embedded, requiring modes of listening and witnessing responsive to situated precarity.

Together, these orientations propose a curatorial praxis that privileges improvisation over instruction, duration over output, and an entangled responsiveness to the temporal textures of local life.

3.3. Speculative Futures and Curatorial Openings

As Song of the Wind moves beyond 2025, it enters a new speculative phase. Rather than scaling up, it turns inward—toward slower, more reciprocal and trans-local collaborations. It emerges not merely as a case study but as a curatorial proposition: an invitation to inhabit the asymmetries of becoming-together. It offers a mode of cohabiting with precarity, deferring closure, and forging solidarities across human and more-than-human difference. These unfinished temporalities do not delineate a singular future but instead invite a plural and processual imagination of co-existence—one shaped not by resolution or mastery but by the openness of becoming-with (Haraway 2016).

Conclusion: Dwelling with Incomplete Rhythms

Through this transnational trajectory, I have examined how curatorial practice—when situated within specific ecologies, temporalities, and affective entanglements—can unsettle the dominant models of socially engaged art (Bishop 2012: 1–20). These dominant models often assume that art should intervene directly in social or ecological problems, and that its value can be assessed through measurable forms of participation or impact. Yet, as the Song of the Wind project illustrates—and as many other comparable socially engaged art initiatives likewise demonstrate—artistic attempts to address socio-ecological issues often expose their own contradictions and limitations (Kim 2014: 299–321).

To some extent, I share the argument that art neither possesses the power to solve real-world problems nor carries the obligation to do so (Kester 2011: 8–11). However, this does not mean that art should refrain from engaging with such issues. Rather, when an artist or curator chooses to address socio-ecological realities, that choice inevitably entails an ethical responsibility – one that requires attentiveness, reflexivity and an ongoing search for ways to respond to, rather than resolve, the conditions encountered.

In this sense, Song of the Wind engages critically with the tension between negative instrumentalism and the idea of art as a relational tool.19 It acknowledges the danger of instrumentalising art – reducing it to a vehicle for external agendas or institutional mandates – while reinterpreting instrumentality as a curatorial and sensory mode of relation.20 Here, instrumentalisation does not signify subservience but denotes art’s capacity to reconfigure communication, perception and cohabitation among diverse agents. Art, in this view, is not a utilitarian instrument for problem-solving but a medium through which ethical encounters and dialogic negotiations can take place.

Thus, Song of the Wind does not seek to ‘solve’ social-ecological problems through art, but to explore how art and curating might inhabit such questions differently. It aspires to cultivate a sensibility of care, responsiveness and ethical attention – one that cannot be reduced to the language of advocacy or resolution, but that opens a shared space for thinking, sensing and living together amid complexity.

The contexts in which Song of the Wind has unfolded – in South Korea, Taiwan, northern Vietnam and Manila in the Philippines – are, of course, markedly distinct. These differences stem partly from disparities in national GDP, historical and social backgrounds, cultural traditions and modes of livelihood. Yet it is striking that people’s underlying perspectives on art, its social role and its ethical potential do not differ as radically as these material and structural conditions might suggest.

What emerges through these field-based encounters is not a coherent or universal model, but a practice attuned to incomplete temporalities: fragmented, asynchronous and often dissonant patterns that mirror the ecological and political precarity of our time. In Lefebvre’s terms, such rhythms constitute ‘the interferences of diverse temporalities’ (1922: 87-88),21 reminding us that artistic processes unfold not in homogeneous time but through entangled, overlapping cadences. To dwell with these rhythms is to recognise that delay, rupture and disjunction are not failures to be corrected but constitutive conditions of collaboration.

In this sense, incompleteness becomes both an analytic and an ethic. It foregrounds a curatorial orientation that resists the closure of resolution and instead cultivates ways of cohabiting with uncertainty. In this sense, incompleteness becomes both an analytic and an ethic. It foregrounds a curatorial orientation that resists the closure of resolution and instead cultivates ways of cohabiting with uncertainty—of inhabiting temporal and ecological knots without seeking premature clarity. In this way, it resonates with Glissant’s call for opacity, wherein relations remain partial, non-transparent, and irreducible to harmony, yet are still generative of shared rhythms of becoming.

Such an approach reframes international collaboration less as a framework for problem-solving and more as a practice of temporal negotiation – a mode of listening across borders, species and uneven conditions of life. It does not presume to dismantle systemic structures directly, but it opens provisional sites of encounter where alternative ways of sensing, knowing and relating may begin to coalesce. Here, temporality itself becomes curatorial22 – an ongoing calibration to the irregular pulses of ecological and social life.

Incomplete Rhythms in Hanoi and Manila

Before moving to the Hsinchu phase, the encounters in Hanoi and Manila further deepened my understanding of ‘incompleteness’. In Hanoi, the inquiry into urban ecology and the colonial legacy of tree planting revealed how ecological rhythms are entangled with histories of migration, modernisation and colonial urban governance. The boundaries between artist collectives and NGOs – most of which operate as social enterprises – appeared fluid and interdependent. This reflects the institutional particularity of Vietnam’s socialist system, where the concept of a ‘non-profit organisation’ does not formally exist. Most cultural and artistic initiatives are defined as social enterprises, and the term ‘foundation’ is rarely used, except in the context of external funding or international collaboration. These structural conditions highlight how socially engaged art in Vietnam is shaped through ongoing negotiations between state frameworks, economic pragmatism and transnational cultural influence.

Within this socio-political environment, attempts to restore Hanoi’s urban ecology and its colonial-era tree-planting heritage have been largely implemented through state-led programmes, international aid initiatives or research projects conducted by foreign universities. However, the local organisations responsible for these efforts are concentrated among a few distinctive social enterprises, whose approaches remain largely pragmatic and administrative. As a result, there are few attempts to reinterpret the issues of ecology and memory through sensory or artistic means, or to approach them as processes of recovering communal rhythm and affect. This absence indicates that the city’s socio-ecological rhythms are being flattened by institutional pragmatism.

I believe that artists could fully participate in these processes. Yet, many social activists I met tended to view artists as people living in a different world – those who create artworks detached from everyday social realities. Conversely, some artists regarded the outcomes of social activism as lacking aesthetic value or formal beauty. This mutual perception of distance reveals how art and social practice continue to delineate their own territories, while simultaneously exposing the potential – and the necessity – of crossing those boundaries.

It is precisely within this gap that Song of the Wind seeks to reexamine the ethical role of artistic intervention and the possibility of social imagination. Rather than attempting to reconcile the distance between art and activism, it explores how to dwell within that very gap – cultivating rhythms of coexistence, responsiveness and care.

In Manila, the sound-based research conducted along the Pasig River revealed how socio-ecological precarity is embodied within the everyday rhythms of urban life. The multiplicity of social movements and local initiatives encountered there also prompted reflection on the ethical and economic complexities that underpin artistic collaboration. Compared to Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam, the Philippines shows a markedly higher level of English proficiency and a heightened immediacy in economic exchange. This immediacy is not merely pragmatic but reflects how collaboration is entangled with broader neoliberal logics of value, exchange and reciprocity. Consequently, the rhythms of cooperation in Manila unfolded through a distinctive temporality – one marked by negotiation, responsiveness and improvisational adjustment.