Introduction

Jiugang, a low-lying islet at the mouth of the Touqian River, offers a vivid glimpse of life negotiated through overlapping rhythms. Fishing practices are attuned to the migration of tides and tidal cycles, while temple caretakers follow lunar rhythms. During peak hours, commuters rush across the bridge connecting the islet to Hsinchu, using it as a shortcut to avoid congested highways. Meanwhile, the broader ecology responds to local cues: the hum of pumps triggered by rising water, the seasonal ebb and flow of shoreline debris and the emergence of fiddler crabs at low tide. Yet these rhythms – embedded in both infrastructure and natural forces – rarely register in the official datasets and metrics that continue to frame the island primarily as a ‘flood-prone zone’, subject to spatial and regulatory constraints that stand in stark contrast to Hsinchu’s rapid urban and technological growth.

My earlier work focused on neighbourhoods in Xizhi, northern Taiwan, a district shaped by recurring floods and its proximity to the Keelung River. In these settings, daily life unfolds around water and is organised by infrastructure, memory and adaptive practices that cater to both seasonal flow and sudden inundations. My research in Jiugang extends this inquiry by engaging with a layered history: once a sediment-filled port and later a shifting fisheries site, the islet now functions informally as a ‘flood buffer’. This unique context provides fertile ground to explore how artistic methodologies can generate alternative modes of ecological dialogue.

The Island of Afterglow workshop was developed as part of the broader Song of the Wind initiative and unfolded in three phases over two days. It included guided night and day walks, as well as a model-making session based on the islet’s geography, including collective reflection. The workshop encouraged site-based attentiveness and explored how observations across time and space might be expressed through material forms and shared narratives. Beyond its methodological role, the project temporarily activated Jiugang Island, fostering public engagement and interaction, and bringing into view ecological and social patterns often invisible within formal representations.

Theoretical Context: Rhythmanalysis and Sensorium

The basis for the Island of Afterglow workshop stems from a fundamental paradox: despite the abundance of climate data, visualisations and environmental monitoring tools, sensing practices often prioritise instrumental outputs over situated knowledge (Gabrys 2016), resulting in limited collective responses to ecological change. Although we frequently encounter scientific graphs, reports and predictive models, a notable gap persists between acquiring information and effectively translating it into collective action or sustainable coexistence. Whether framed in terms of anthropocentric perspectives or broader environmental alienation, central questions remain: How can we engage environmental phenomena in affective, aesthetic and collaborative ways? What alternative methods can bridge the gap between abstract data and embodied experience?

To approach these questions, Island of Afterglow primarily draws upon Henri Lefebvre’s (2004) ‘rhythmanalysis’, a conceptual framework that focuses on observing and interpreting the rhythmic dimensions of everyday life. Lefebvre defines rhythm as energy deployed within specific times and spaces, encompassing bodily processes such as breathing and heartbeat, daily routines, urban flows and cyclical natural events. For Lefebvre, rhythm is shaped by the dialectical relation between repetition and difference, with each cycle involving subtle variations that contour lived experience.

Central to Lefebvre’s rhythmanalysis is the idea that the analyst’s own body serves as a primary analytical instrument, functioning as a sensory reference point for perceiving and interpreting rhythms within a specific environment. The rhythmanalyst actively engages their surroundings through multisensory perception, utilising hearing, sight, smell and touch to detect subtle ecological and social rhythms.

In the Island of Afterglow workshop, participants were guided to heighten their sensory awareness of breathing patterns, walking pace and environmental sensations. These embodied perceptions provided fundamental reference points for recognising and analysing the ecological and infrastructural rhythms of Jiugang Island. Lefebvre’s conceptual categories – eurhythmia (harmonious rhythms), arrhythmia (disruptive rhythms), and polyrhythmia (multiple coexisting rhythms) – were introduced as interpretive tools rather than fixed classifications. Participants thus developed observations and interpretations grounded in embodied, sensorial experiences, enabling creative engagement with the island’s socio-ecological context.

Complementing Lefebvre’s rhythmanalysis, Caroline A. Jones’s (2006: 14–16) concept of the ‘mediated sensorium’ highlights how modern perception is shaped by both cultural–historical contexts and technological mediation. Jones suggests that contemporary artistic practices employing multisensory immersion, as well as narrative and experiential interventions can reveal and reconfigure technologised sensory biases in everyday life, which aligns with the workshop’s use of embodied, participatory methods (e.g., sensory walks, tactile modelling, collective mapping and 3D scanning) to foreground how perception is materially and culturally produced.

The workshop’s theoretical approach further aligns with interdisciplinary practices, including sensory ethnography which focuses on embodied perception of environments (Ingold 2000), examples of socially engaged art that highlight community–based ecological engagement (Thompson 2012) and autographic visualisation methods for materially tracing environmental processes (Offenhuber 2016). Collectively, these frameworks support the workshop’s integrative approach, emphasising embodied and sensory methodologies as mediators between abstract ecological data and lived, local experiences.

Fieldwork Context: Jiugang Island

Jiugang Island lies at the confluence of the Touqian River and the Taiwan Strait, on the periphery of Hsinchu City. Historically established as a trading port during Japanese rule (1896–1930s), the island gradually lost its maritime function due to sedimentation, leading to a shift toward small–scale fisheries and informal residential development.1

Today, Jiugang’s landscape comprises overlapping socio–ecological layers: its flood–control infrastructure, fisheries, and architectural patterns based on elevation–based housing restrictions in the designated flood–buffer zone that prohibit new permanent structures on land less than 50 cm above the designated base elevation.2 These constraints shape everyday life. Oyster and eel fishing, for instance, is subject to tidal and migratory rhythms. At the same time, residents adjust their home lives and daily routines to accommodate pump operation schedules and water-level monitoring.

A key mediator on the island is DaoGangFengChao,3 a community empowerment unit based at the former Coast Guard station (Figure 1). It serves as a creative hub and educational base, organising environmental walks, community farming initiatives, river–crossing events and art festivals. Preservation efforts in fishing villages like Jiugang are not only rooted in the daily needs of residents but are also driven by the development of tourism (Tai and Kang 2007). Their emphasis on community-led practices supports the workshop’s research objective of balancing historical frameworks with adaptive living strategies by means of selected walking routes and discussion topics.

These community-based insights guided the Island of Afterglow workshop. Working closely with DaoGangFengChao, local residents and educators from Hsinchu Community College, we co–planned routes and activities. Our daytime and nighttime walks were mapped during joint field visits, and we intentionally avoided restricted areas to ensure accessibility. The walks explored levee breaches, temple courtyards, tidal flats and historic port–perimeter paths – each rich in history – as well as infrastructural boundaries and environmental narratives .

Workshop participants, from both Jiugang and the greater Hsinchu area, brought diverse backgrounds and perspectives. By integrating the design of activities with Jiugang’s spatial–historical dynamics, the workshop encouraged participants to experience local rhythms not as separate phenomena but through movement, sensory engagement and co–created storytelling and modelling. By adopting this approach, Jiugang served not just as a setting but as an active participant, influencing both the logistical setup and the conceptual framework of the workshop.

Methodology: A Participatory Approach for Field-based Inquiry

Co-planned with DaoGangFengChao through a series of iterative field meetings, the workshop unfolded in three interconnected phases: Nighttime Walk, Daytime Walk, and Islet Model Making and Sharing. Rather than importing a preset template, the programme grew organically from ongoing local dialogue, prioritising accessibility while extending the island’s existing initiatives and community momentum.

Recognising the complexity of working within a semi–informal settlement, we adopted an open participatory model grounded in care and responsiveness. Instead of recruiting a fixed group of participants, the workshop welcomed diverse residents and visitors from Jiugang and Hsinchu, allowing flexible forms of involvement. Acknowledging the plurality of perspectives within Jiugang, elders and residents were invited to share their own stories and sensory knowledge. Rather than speaking for the island, their contributions foregrounded lived experiences that coexisted with other situated viewpoints.

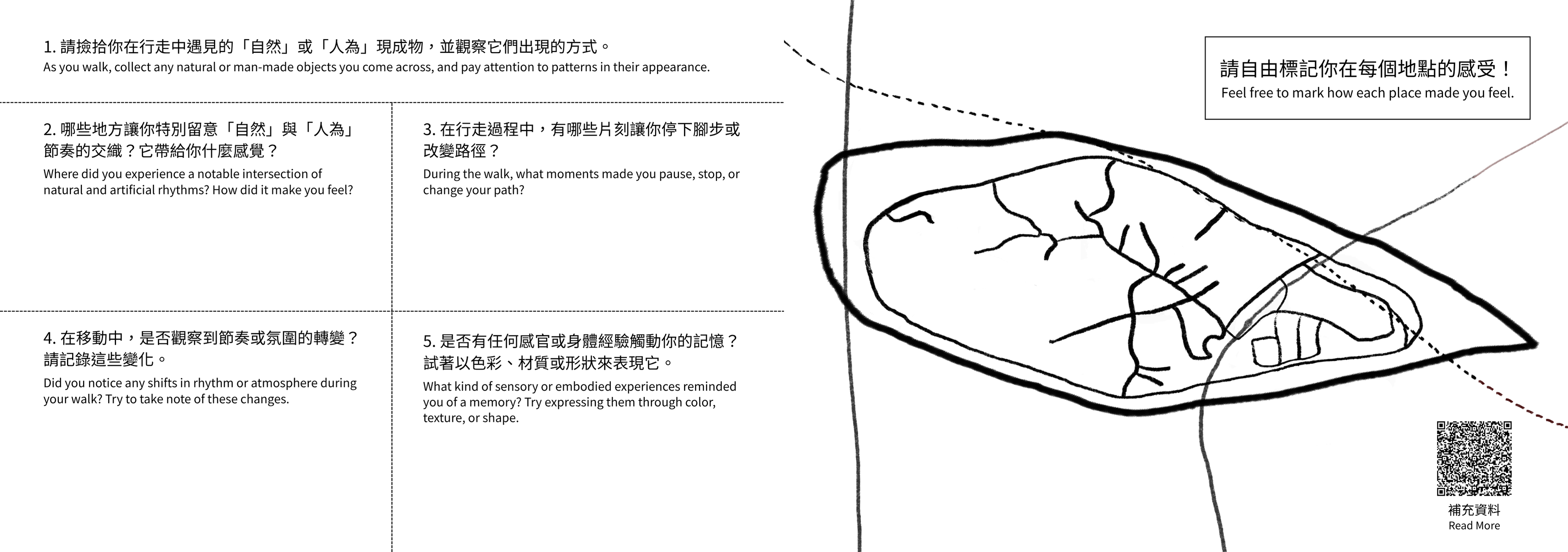

Participants were provided with a structured yet adaptable ‘Instruction Card’ (Figure 2), designed explicitly for all workshop phases, to guide them in documenting sensory observations and reflections. Prompts included noticing intersections between natural and human–made rhythms, shifts in embodied or emotional states and sensory triggers that evoke memories, supporting consistent yet flexible documentation of experiences across the programme’s activities.

Nighttime Walk (21 June, 19:00–21:00)

The nighttime walk was designed to explore Jiugang Island’s socio‑ecological dynamics through multisensory engagement under conditions of reduced visibility. Preliminary visits indicated that nighttime illumination on Jiugang Island differs significantly from the brightly lit urban core of Hsinchu City. Due to the absence of commercial lighting and the predominance of residential streetlights, Jiugang’s nocturnal environment is uniform and minimalistic. This limited lighting restricts mobility and distinctly shapes sensory perceptions, and the experience is accentuated by visual and auditory contrasts with illuminated industrial facilities and continuous traffic on opposite riverbanks.

Guided by local elders and community members, participants traversed a planned route through Jiugang’s residential areas, river levees, temple courtyards, a community food forest and spaces beneath Jiugang Bridge. At these locations, residents shared stories about the local infrastructure, labour practices, community life and flood memories, providing essential social and historical context for sensory exploration (Figure 3).

Participants then collaborated in small groups to share performative narratives using portable lights, natural materials and LED strips. These brief performances, presented at specific sites along the route, translated multisensory observations into tangible expressions, collectively articulating Jiugang’s socio–ecological rhythms (Figure 4).

Daytime Walk (22 June, 10:30–12:00)

In contrast to the nighttime session, the daytime walk emphasised tangible environmental and historical traces, enabling direct engagement with Jiugang’s layered socio–ecological context. Participants traversed informal fishing paths, visited historical sites such as the former Tamsui Customs Office, intertidal zones, ecological farms and residential areas subject to flood–zoning regulations. These sites were selected to visibly demonstrate interconnected environmental, cultural and infrastructural dynamics.

Along the route, residents and elders shared personal and historical accounts, highlighting how shifts in infrastructure and ecology have shaped local life. Their narratives emphasised interactions between human practices and natural processes, illustrating the impacts of flood–control measures, sedimentation and tidal cycles (Figures 5 and 6).

Using the structured yet adaptable instruction cards (Figure 2), participants systematically documented sensory perceptions and material traces, including driftwood, shells, plastics and found artefacts. These physical traces revealed interactions between ecological elements such as wind, water and weather, and human interventions. Participants noted the intersections of natural and artificial rhythms, sensory triggers that prompted pauses or route adjustments and shifts in bodily or emotional states.

This documentation produced a rhythmanalytical inventory, capturing both material artefacts and embodied interpretations of Jiugang’s temporal and environmental complexities. These tangible records provided a foundation for the subsequent reflective model–making session.

Islet Model-making and Sharing (22 June, 13:00–15:30)

The final session invited participants to translate their earlier observations and collected materials into tactile island sculptures, structured by four thematic prompts: ‘Emotional Landscape’, ‘Rhythmic Imprint’, ‘Narrative of Structure’ and ‘Embodied Mark’. Each thematic prompt guided participants in identifying specific materials, forms and concepts derived from their sensory fieldwork (Figures 7 and 8).

For the ‘Emotional Landscape’, participants used acrylic paints to create a visual atmosphere that reflected their overall impression of Jiugang’s spaces. Colours represented emotional states; for example, tranquillity might be depicted with blue or green, while isolation could be expressed through muted or darker tones (Figure 9).

For ‘Rhythmic Imprint’, participants juxtaposed found objects such as leaves, stones, nails and tiles, which reflected concerns about tensions between human activities and natural environments. They used coloured pens and fluorescent paints to indicate intangible rhythms, including wind, tides and transitions between day and night. For example, these dynamics were articulated through shells combined with screws, wavy lines representing wind and dots in fluorescent colours illustrating nighttime illumination.

For the ‘Narrative of Structure’, participants used materials such as clay, string and pins to construct spatial boundaries that represented local infrastructural elements, including levees and roads. These structures symbolised relationships between humans, water and spatial management, informed directly by residents’ stories of flooding and infrastructural change collected during the walks.

Lastly, the ‘Embodied Mark’ prompt asked participants to depict direct sensory interactions with Jiugang’s environment. Using contrasting textures such as soft cotton, rough sandpaper, smooth stones and coarse driftwood, they mapped tactile experiences onto their models. For example, cotton might symbolise the sense of comfort associated with gardens, whereas sandpaper or rusted metal could signify unease in areas of infrastructural decay, while written annotations on the sculptures served to highlight encounters and to transform impressions of the environment into tangible ideas.

Upon completion, participants 3D–scanned their sculptures using LiDAR–equipped mobile devices, capturing precise textures and material nuances that facilitated detailed preservation and accessibility of embodied experiences (Figure 10). Participants then shared their models, engaging in collective discussions that articulated interpretations of Jiugang’s environmental rhythms, personal narratives and historical memories. These sculptures thus functioned as tactile interfaces, bridging sensory perception and collective socio–ecological dialogue.

The digitally documented sculptures offer ongoing potential for broader community engagement. They can be integrated into community practices such as augmented-reality experiences, ecological forums or comparative discussions with other estuarial communities, linking embodied sensory awareness with broader socio-environmental contexts (Figure 11).

Findings and Reflections

Through guided walks and model–making, participants transformed environmental cues such as tidal shifts, wind patterns and infrastructural cycles into tangible artefacts. Several thematic patterns emerged:

Personal and Affective Rhythms

Some participants expressed personal and emotional connections to Jiugang’s environment. One model, ‘Christmas Rainbow Island’, employed glitter, crushed leaves and small candles to represent comfort, warmth and cyclical rhythms. Another participant created two islands connected by distinct paths, one broad and leisurely and the other composed of playful stepping stones, to contrast coexisting tempos. These personal expressions illustrated how rhythm allowed participants to negotiate emotional attachments to place.

Structural Tensions and Sensory Disruptions

Other participants highlighted tensions within Jiugang’s socio–material context. One participant contrasted soft cotton with rusted iron, evoking discomfort linked to infrastructural decay and exposure. Another produced an illustration of oppressive midday heat through a radial ink pattern, visualising the atmospheric constraints on comfort and movement. These examples reflect Lefebvre’s concept of ‘arrhythmia’, where conflicting rhythms necessitate bodily adaptation and interpretation.

Temporal Traces of Environmental Change

Several participants addressed Jiugang’s layered ecological memory by materialising temporal patterns. One sculpture used concentric metallic rings to represent historical flood levels based on oral accounts from local elders. Another combined driftwood, shells and plastics to depict tidal processes and gradual debris accumulation. A third model contrasted natural erosion (rounded driftwood) with human interventions (corrugated iron), emphasising differing rates of ecological and infrastructural change.

Together, these findings demonstrate how embodied field practices, rooted in material engagement, can transform abstract ideas of time and environmental patterns into concrete expressions. Rather than dictating meaning, the workshop encouraged various forms of attunement, allowing rhythm to serve as a lens for diverse, place–specific expressions.

Discussion

The Island of Afterglow workshop avoided artist–led or theory–driven formats. The goal was to gather diverse local responses to Jiugang Island’s socio–ecological context by collecting insights from residents and visitors with different backgrounds, aiming to inspire future research that aligns with the broader goals of the Song of the Wind initiative.

Participants were recruited without fixed criteria, leading to a diverse mix of ages, educational levels and expertise. This diversity resulted in varied thematic interests, making it challenging to establish a clear focus. While common themes such as anthropocentrism were not explicitly highlighted, some participants explored them on their own. This approach fostered an inclusive environment, allowing discussions to mirror participants’ personal experiences and priorities, even though there was limited theoretical depth or cohesive narrative.

The workshop preparations facilitated inclusion of diverse perspectives, experiences and practical considerations from participants and local partners, ensuring responsiveness to Jiugang’s specific infrastructure and environmental conditions. To systematically gather participants’ insights, feedback surveys were distributed, allowing for structured evaluation and reflection on the activities and their effects.

However, the openness and broad scope of the activities introduced methodological challenges. Participants came with varying degrees of familiarity regarding Jiugang’s historical context, regulatory frameworks and policy considerations. Some were highly involved with the site, regularly participating in local activities or belonging to advocacy groups, while others visited for the first time or had different levels of arts–related experience. Consequently, interpretations shared during discussions were influenced by participants’ varying degrees of engagement and familiarity with the themes and methods at stake, as well as by perspectives provided by local partner organisations. While recognising these inherent limitations, the workshop consciously avoided imposing theoretical frameworks or predetermined conclusions, allowing interpretations to emerge organically from participant interactions and situated knowledge.

The central role of rhythm in the workshop’s design and analysis, articulated as ‘Attuning to Rhythms’, was intended as a methodological approach. Drawing on rhythmanalysis, rhythm served as a practical tool to observe, experience and express temporal and spatial interactions without resorting to complex theoretical language. Attunement was put into practice through embodied sensory methods (walks, modelling, sharing), helping participants to notice and respond thoughtfully to patterns and changes in their environment. In this way, rhythm was not just a metaphor but a practical, accessible way to connect participants’ embodied experiences directly to Jiugang’s infrastructural, ecological and social contexts.

Thus, the workshop demonstrated how participatory methods focusing on sensory and rhythm–based activities can connect abstract environmental concepts with a range of lived experiences. Although there are inherent methodological limitations, this approach established a foundation for future community–focused research and interventions that are adaptable and responsive to local contexts and needs.

Conclusion and Future Directions

This article demonstrates rhythm as a generative methodological framework for site-responsive artistic research, bridging the gap between abstract environmental data and embodied ecological experience. Through the Island of Afterglow workshop, rhythm was operationalised as both a practical method and an interpretive metaphor, allowing participants to articulate Jiugang Island’s socio-ecological rhythms through tangible, participatory forms.

The workshop provided a replicable model of rhythm-oriented inquiry, integrating sensory-based fieldwork (walks and model-making) with collaborative dialogue and local narratives. By offering structured yet flexible tools including instruction cards, tactile models and LiDAR scans, participants generated artefacts that translate individual sensory perceptions and community knowledge into accessible resources for future use.

These outcomes offer significant potential for further application. Digitised models and documented sensory narratives can serve as adaptable interfaces for community education, ecological consultatio, comparative studies and augmented–reality engagement. Within the broader Song of the Wind initiative, these materials may support ongoing dialogue around flood management, spatial governance and environmental change.

Future extensions of this methodology could include seasonally embedded studies to observe rhythmic variations over time, thematic workshops addressing specific environmental challenges (e.g. sedimentation, heat stress, water governance), and cross–modal experiments such as sonic interpretations of local ecological data and community narratives. Such directions align with the overarching aim of cultivating context–sensitive strategies for ecological participation and stewardship.

In summary, rhythm, when approached through embodied, participatory practice, provides a relational vocabulary for negotiating diverse perceptions, experiences and knowledges about socio–environmental conditions. As ecological challenges grow increasingly complex, such methods offer practical pathways toward deeper, locally grounded ecological awareness and responsive community engagement.

Endnotes

- Jiugang was officially established in 1896 as one of Taiwan’s eight special entry and exit ports during the Japanese colonial era, ceasing operation in the 1930s due to progressive river silting and ecological transformation. ↩

- Under the Hsinchu City Government’s recent zoning regulations, new construction within Jiugang Island’s designated flood-buffer zone is permitted only on land elevated by more than 50 cm from the official base level. These rules seek to retain the area’s flood-water capacity, yet they have inadvertently encouraged informal housing and regulatory uncertainty. ↩

- DaoGangFengChao was established in 2023. See: https://jgdisland.blogspot.com ↩

Po-hao Chi is an artist and cultural producer from Taiwan, and the founder of ZONE SOUND CREATIVE, a studio dedicated to the convergence of music, technology, and art. Treating sound not merely as an object of listening but as a structuring force that shapes temporality, spatiality, and socio-political experience, his practice spans installation, performance, field recording, and writing. Influenced by cybernetic and ecological thinking, Chi explores how rhythm – through repetition, circulation, and variation – mediates the porous boundaries between the human and non-human, the subjective and the infrastructural, revealing how technological infrastructures shape collective sensory and affective conditions.